Two weeks ago, we released our 2023 Review and 2024 Outlook, where we discussed our outlook for 2024.

This piece will be different as it reflects on ideas that, while important, get unfairly pushed to the backburner. Over a slightly-longer format, join me as I share some of my thoughts on a variety of topics shaping longer-term trends in markets and the investment landscape.

In 1983, approximately 2 years into my career as a 'Customer’s Man' (the historic name for what is now referred to as ‘Financial Advisor'), the Fed’s balance sheet held slightly less than $200 billion of securities, which represented roughly 5% of GDP. Forty years later, with greying hair, I spy that same balance sheet laden with nearly $8 trillion of securities, the equivalent of a much heftier 29% of GDP. Needless to say, the Fed of my earlier career is a totally different institution from the one we have today.

As a result, investing in today's markets must incorporate the high likelihood of meddling from an activist Fed that’s proven far more intrusive than in prior eras. The current generation of economists and monetary policymakers have clearly demonstrated that they regard frequent 'shock and awe' intervention as a legitimate tool to cure economic ills. Consider the veritable 'alphabet soup' of programs that was established simply to address the market shocks resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic:

We can recall a similar set of acronyms from the response to 2008's Great Financial Crisis (TARP, TALF, etc.). More recently, 2023 saw the establishment of the 'BTFP,' or Bank Term Funding Program (in case you missed it, this was designed to bail out the March 2023 regional bank crack-up).

While only some of these programs ultimately got utilized by market participants, it was their very presence (along with the implication of a Fed backstop) that had the most impact on markets. In today’s investment climate, every emergency comes with its own tailor-made intervention.

This leads to a challenging dilemma: are we to invest assuming this new paradigm is the 'new normal,' where the Fed stands ready to bail out unsuspecting and professional investors from the perils of market volatility? Or will the Fed only take unrelenting action in the most serious situations (eg: 2008 and 2020)? Either way, shall we assume this incentivizes more risk-taking?

To this observer, we'll continue investing with our eyes wide open and expect no handouts from the Fed.

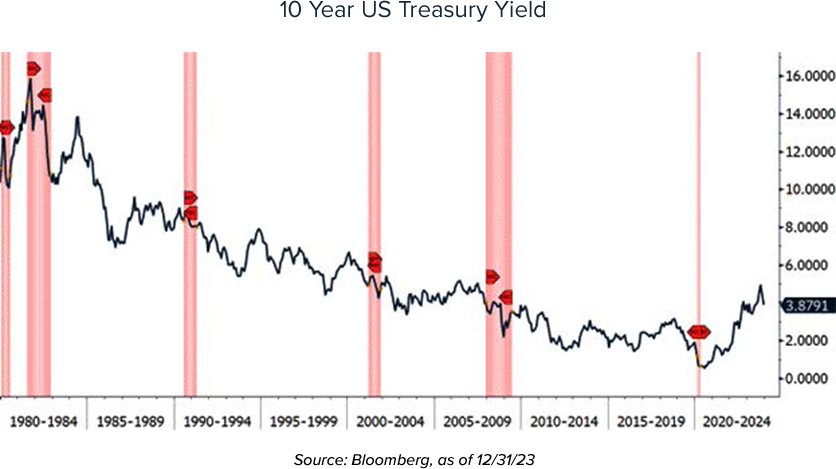

I've always viewed the price of money (i.e. the level of interest rates) as the speed regulator for economic activity. The higher the price, the more the economy's brakes get tapped; conversely, lower rates of interest push down ever harder on the economy's accelerator. It's not always this direct or simple, but more often than not it's what I've observed.

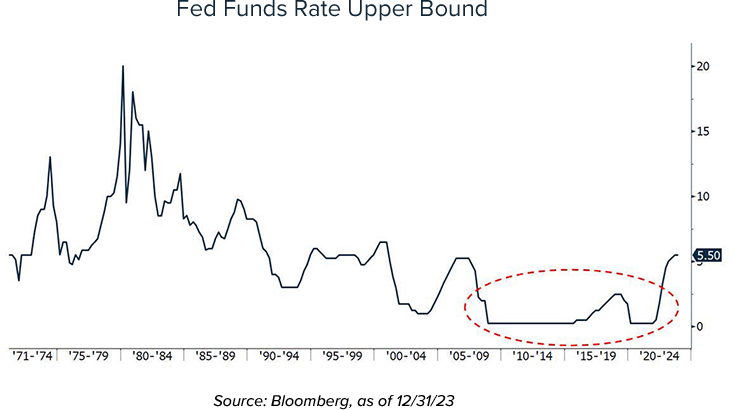

Recognizing that radical action was necessary to address the immediate shock of 2008's GFC, we applauded Chairman Bernanke for implementing the then-novel emergency tactic of Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP). ZIRP was as simple as it sounds – it brought the Fed Funds rate down to nothing (read: zero) and kept it there, quickly revving the economy's engine to stem the bleeding. As if zero interest rates weren't enough, the speed of stimulus was accelerated by purchasing bonds in the open markets (QE), which further brought down fixed income yields and added even more liquidity to an already-frothy monetary environment.

Since interest rates get into every nook and cranny of the economy, a 0% benchmark yield means free money for all. And the free money undoubtedly boosted corporate and consumer spending and borrowing. But like any strong medicine it had major side effects including outsized speculation and leverage.

Combined with the actions of the other major global central banks (some of which were even more aggressive in pushing the monetary envelope), the obvious signs of market distortions abounded.

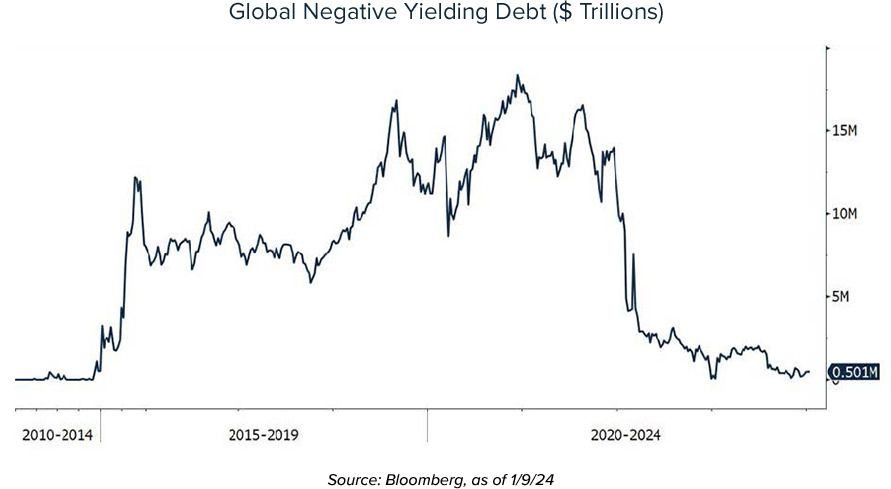

Perhaps the most staggering example was the emergence of a new phenomenon - negative-yielding debt, which metastasized to infect an unbelievable $18 trillion worth of global bonds. Although negative yields luckily never reached our shores, their impact from abroad certainly did.

The risk-reward tradeoff of ZIRP (along with Quantitative Easing and related measures) was justifiable in the context of a true crisis, but clinging to these policies for the better part of 14 years was unnecessary.

I have little doubt that policymakers' attempt to centrally manage the level of interest rates for so long proved fateful in ushering in the most stunning rise in inflation in 40+ years.

Adding fuel to the fire, in the summer of 2020 those same 'Monetary Mavens,' backed by legions of Ph.D economists, were concerned that 0-2% annualized inflation was running too far below their (randomly chosen) 2% per year target. The 'solution' to this 'problem' was a new Flexible Average Inflation Targeting policy, whereby they publicly announced that future inflation above 2% for some time (e.g. to 3-5% for a few years) would be tolerated, if not outright encouraged, to achieve a new goal of precisely 2% inflation 'on average.' Brilliant.

Well, I suppose their generous self-regard finally took a backseat when inflation started printing at 8-9% in the first half of 2022 (after the 5-7% prints of 2H 2021 hadn’t broken their monetary spirits). It took a generational fiasco for the Ph.D economists to realize they had to begin quickly reversing their failed policies. In a stunning (and admittedly applause-worthy) about-face, the Fed began peeling the Fed Funds rate off the floor in Q1 2022 and methodically got it above 5% in a very short 18 months.

On the positive side, we're now clearly seeing inflation decline while economic conditions - at least for now - remain brisk. But this entire sequence of events hasn't exactly 'fostered price stability' (which is half of the Fed's dual mandate). Market stability has been questionable too; as we wrote a couple of weeks ago in our 2023 Review and 2024 Outlook, stocks got pummeled in 2022 but surged in 2023 thanks almost solely to the returns of the 'Magnificent 7' group of mega-cap tech companies. Bonds, needless to say, got pummeled in 2021, 2022, and for most of 2023 before a screaming rally lifted bond prices (and reduced yields) in November and December.

As clients and longtime readers know, in general, we marginally scaled back equity exposures in 2022 and reallocated proceeds into long-term, high-grade bonds throughout 2023, seeking to lock in elevated yields.

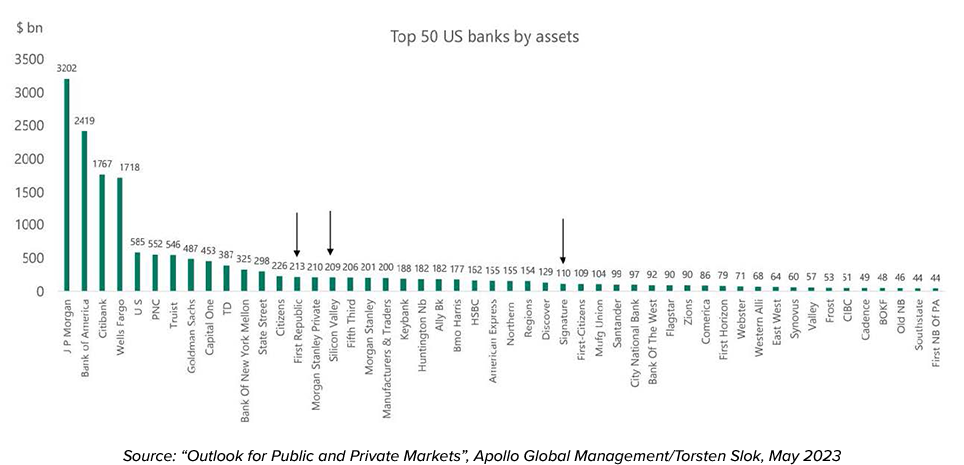

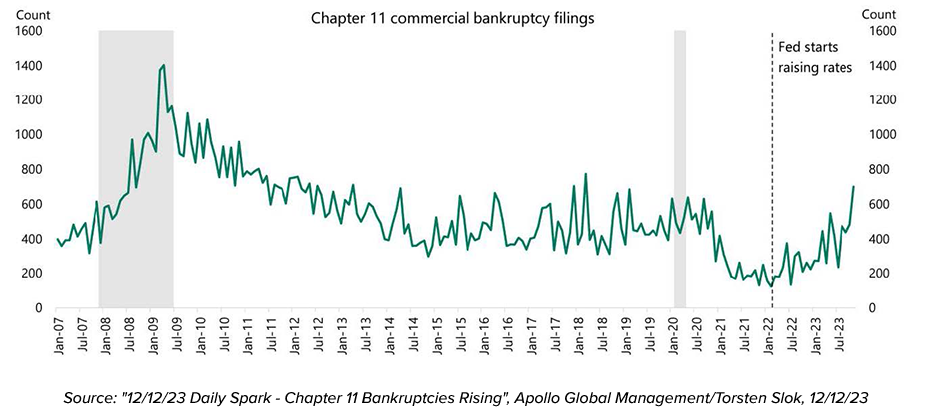

More ominous are the potential longer-term consequences. Like easy money, Fed hiking cycles are strong medicine with their own well-known history of side effects. The graveyard of failed entities is starting to swell; for example, 3 of the top 30 US banks by assets failed in 1H 2023 (First Republic, Silicon Valley, and Signature Banks).

Non-financial businesses are just beginning to feel the pain now, as bankruptcy filings are rapidly trending higher:

The Fed and markets now believe in the inevitability of a so-called 'Soft Landing:' where inflation declines towards the 2% target while the economy suffers only a negligible slowdown (i.e. no recession) with just a slight uptick in the unemployment rate.

Decades of plowing the investment fields have caused me to grow cynical of rosy outlooks, especially when it comes to the Fed’s ability to control the economy with precision.

Needless to say, I'm skeptical they'll be able to stick the landing on the USS Powell. So far, I've been surprised at how resilient the economy and earnings have held up. But managing wealth is a long game - especially when the return of capital is more important than the return on capital. Sooner or later, it's possible that things will go sideways, and it pays to prepare ahead of time.

It's why, in 2023 and as the calendar turns to 2024, we're positioning portfolios to benefit from a slowing economy. That means, in broad strokes, reducing exposure to illiquid hedge funds (both multi-strategy and single-strategy) and maintaining extended maturity profiles in bond portfolios. Since long-term interest rates recently declined from appr. 5.00% to 3.8%, we've suspended extending maturities for the time being.

It would be unfair if I focused all my concerns solely on the Fed's economic malfeasance – Washington, DC's fiscal policymakers have made plenty of their own egregious mistakes in recent years.

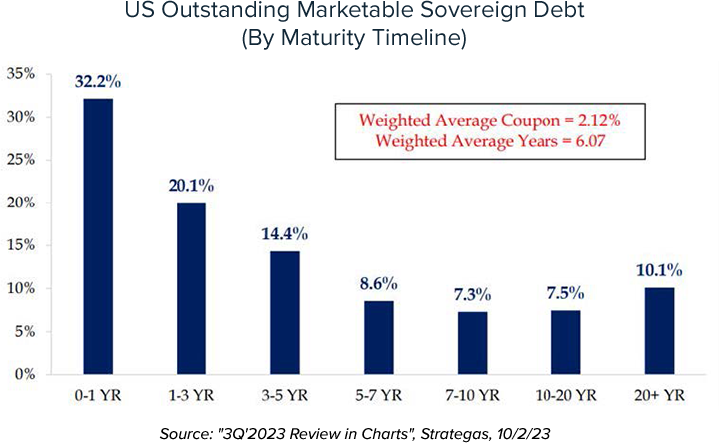

The most obvious error was missing the multi-year opportunity to extend the maturity profile on our Federal debt (US Treasuries) when rates were near zero. Many other rational people and institutions didn’t miss the boat. Certainly, we all know people with sub-3% mortgages. Trillions of dollars' worth of corporate bonds were issued with historically low coupons. Even other governments got the memo: in 2020, the Government of Austria issued a 100-year bond at a coupon rate of just 0.85%.

But someway and somehow, news of the historic rate opportunity never reached DC and we never issued ultra-long-term Treasuries at ultra-low rates. Now, over half of our federal debt matures over the next 3 years, and will be rolled over in a much higher interest rate environment.

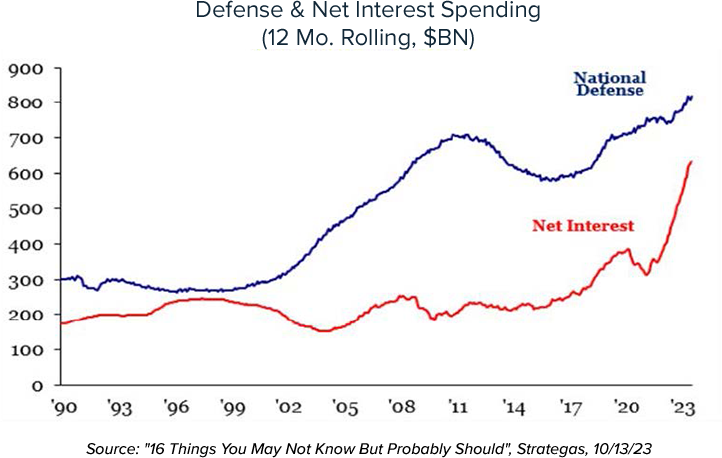

This means we're staring down the barrel of interest expense beginning to consume an ever-larger proportion of Federal government spending, inevitably crowding out expenditures in other vital categories. Consider this: in just the next few years, it's highly likely that net interest outlays will be higher than the size of our entire defense budget. This likely leads to even wider budget deficits that must be plugged with yet more Treasury bond issuance.

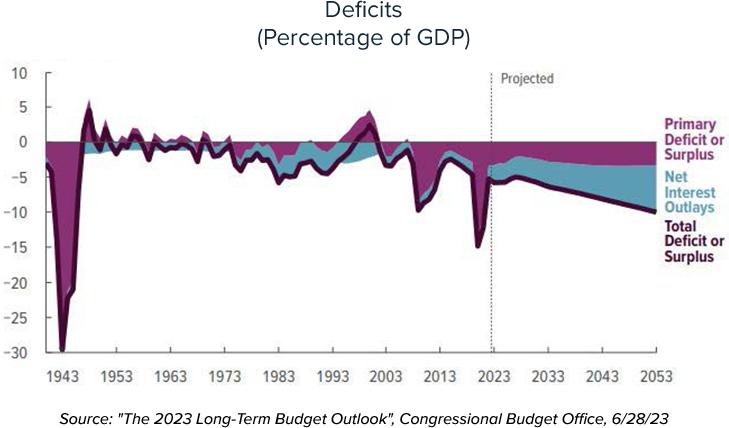

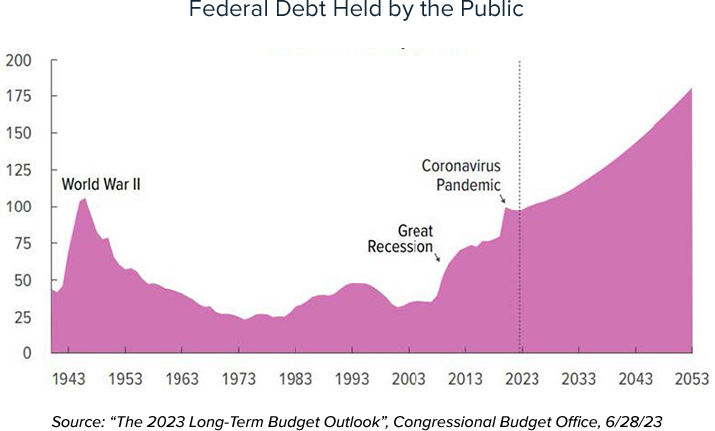

Even Congress' own math shows the Federal budget deficit is only slated to get worse from here.

One of our research providers, Anatole Kaletsky at Gavekal Research, recently pointed out that the US generates approximately 40% of the world’s total government budget deficits with just 4% of the world’s population. Suffice to say nobody could accuse us of being spendthrifts.

The worse news is, if locking in low interest rates wasn't embraced, rampant spending certainly was. Since 2020, we've witnessed a Washington, DC spending free for all:

If that wasn't enough, this doesn’t include the ultimately abandoned Build Back Better Act ($2.2 trillion) and potential forgiveness of federal student loan balances ($500 billion).

Anybody could argue for or against the fundamental merits of any of these initiatives – that's not our point. The problem is that DC has become addicted to unsustainable amounts of deficit spending.

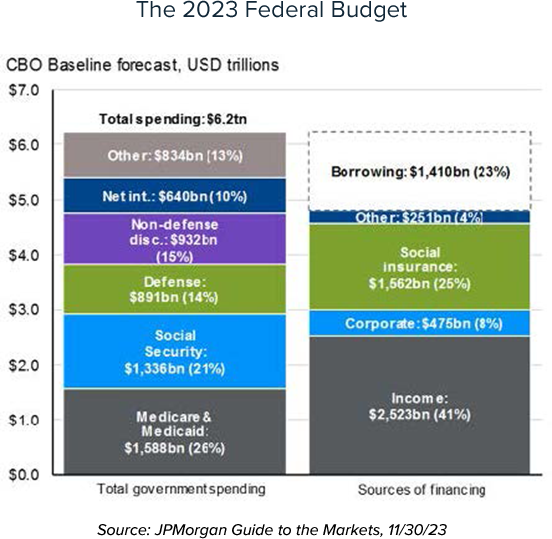

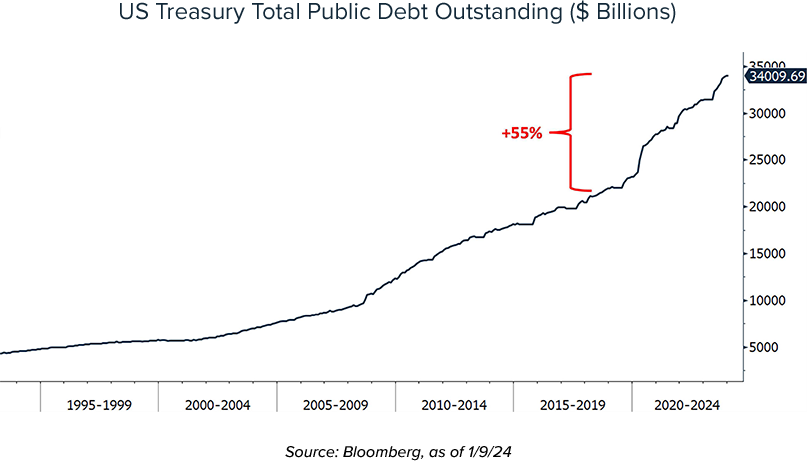

As things stand, the federal government is short approximately $1.4+ trillion annually against a total budget of >$6 trillion – a whopping (and ever-growing) hole that must be funded by continually issuing Treasuries. As more Treasuries are issued, the cost of servicing existing and new debt continues to climb, thereby consuming more and more of the Federal budget – a self-reinforcing negative feedback loop.

At the same time, Powell and Co. at the Fed are no longer adding to their massive stockpile of Treasuries (accumulated during the QE years), and are in fact now allowing them to mature and roll off the balance sheet (QT). So, it's a double-whammy; the Treasury has to issue bonds to pay off the Fed as well as fund an ever-expanding deficit.

What gives? Well, markets have taken notice. At the time of this writing in mid-January, global 10-year sovereign bond yields are changing hands well below US Treasuries (4.00%). As an example: Greek government 10-year notes trade around 3.30%, Italy's at-3.80%, Portugal’s at 2.90%, and Spain's at 3.10%.

As investors, we must now handicap the relative strength of two competing forces: that of a slowing economy which would push rates lower against a massive schedule of upcoming Treasury issuance which could require higher rates to attract price-sensitive buyers.

It wasn't always this way – the debt binge is a relatively recent phenomenon, only really accelerating in recent years.

In Q1 2019, our national debt was $22 trillion. Today it sits at $34 trillion, a 55% increase in just 5 years. The federal government added as much debt over the past 10 years as it did over the first 247 years of this country's existence.

In the long run, are we to manage client wealth under the assumption that the federal government will continue to degrade our economic vitality by running deficits and issuing massive amounts of Treasuries? More concerning, how will policymakers have the room to react if unemployment surges and society calls for increased funding on social programs, while we're already running the largest peacetime deficits in history? At what point will the risk of the US dollar acting as the global reserve currency diminish?

Our current positioning moderately reflects our concerns for many of these potential outcomes.

Interest rates were effectively zero from 2008 through 2022. This meant bonds provided little return, and no protection in a diversified portfolio against the threat of a falling stock market. Savers were penalized and retirees were forced to hold riskier investments (e.g. stocks) in an attempt to meet portfolio goals. Asset allocations were biased towards equities, whether or not that made the most sense for clients in more 'normal' times.

At the same time, an army of newly-minted college and MBA graduates first joined the ranks of Wall Street in an environment where money had no cost and borrowing to buy anything made perfect sense. This went on for 14 years, and we must now contend with an investment community partially comprised of market professionals under 35 years old who have never really seen an investible bond market, let alone the impact of rising interest rates.

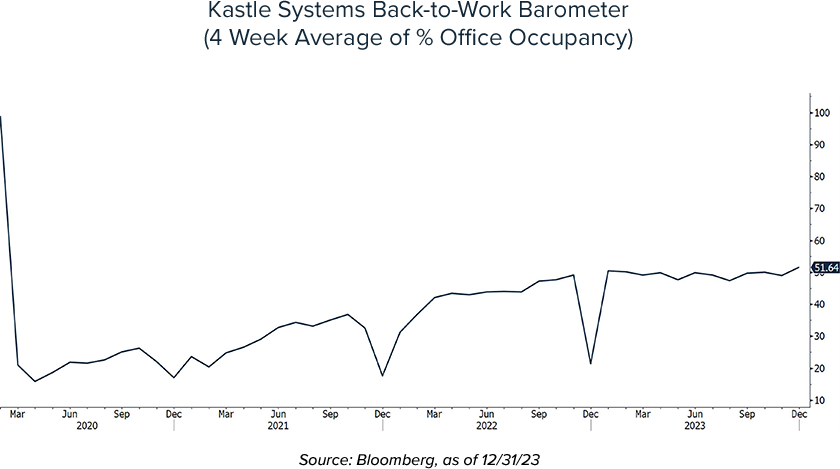

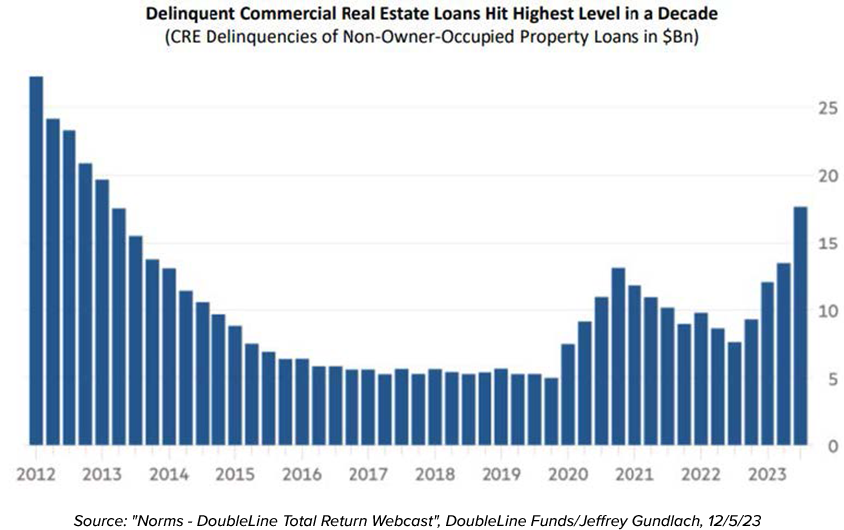

This has significant implications for personal interactions, one-on-ones, and impromptu collaborations. Call me old school (along with cynical), but I believe workplace culture is important and it doesn't evolve easily. WFH can certainly be a time saver for long commutes and assist families juggling the gymnastics of raising kids. But what's the long-term impact on investment decision making? Will the lights stay on in the half-filled office buildings littering cities across the country? We've seen increasing stress on commercial real estate loans, a segment of the market that's turning into a real slow-rolling disaster.

In this case, age does have a benefit. The return of a more 'normal' rate environment is a wonderful opportunity for investors: less-risky portfolios can now own bonds with actual yield. Remember: 5% annual returns means that a portfolio doubles in approximately 14 years (excluding taxes and withdrawals).

But the big question remains: are we now facing a paradigm shift to structurally higher rates, or will the Fed revert back to its emergency policies (again) at the next whiff of a slowdown? Will we see zero yields once more? I don't think it will happen - but on the flipside, I wouldn't be surprised if the 10 year Treasury trades below 3% at the bottom of this particular cycle.

If you don't know what this acronym means, you've likely avoided all print or media for the past 3 years.

Talk about a paradigm shift! I'm still a pendolare and before catching my Metro North train bearing 2 newspapers (yes, print-virtually extinct), I can gauge the WFH percentage after turning into the parking lot of my station. Most days, it's substantial.

Alternatively, will office workers instead begin to scramble back into the office if the unemployment rate ticks back up to 5% and employers enforce Work-From-Office mandates? In that case, perhaps I'll once again have trouble finding a seat on the train.

The investment landscape has changed markedly over the last 40 years, as it indeed should. But it hasn't all been for the better. The Fed has greatly extended its reach into markets and Washington seems oblivious to the long-term risks of borrowing money. Bond market volatility is elevated while stock market performance is now concentrated into a narrow group of names (e.g. as seen in the news, the 'Magnificent 7').

Are these just passing fads, or more durable paradigm shifts? Either way, we remain highly focused on the impacts of these changes. Our team reaches broadly to surveille the landscape, seeking clues by turning over many rocks, all part of a never-ending effort to better inform our thinking and decision-making on behalf of clients.

We appreciate your ongoing trust and confidence in bestowing on us the

opportunity to manage your wealth.

-Richard Saperstein