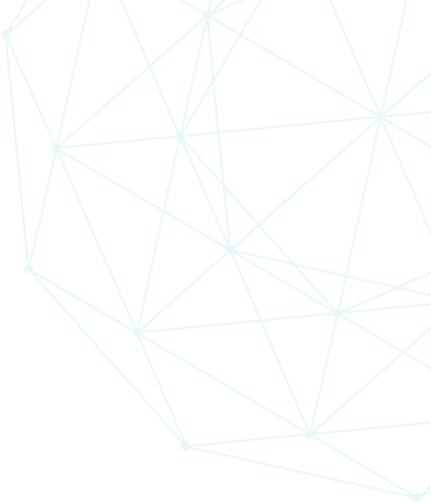

We recently raised the interesting observation that the 10-year Treasury yield hit its absolute peak of 15.84% exactly 40 years ago (see Alert: Fed Tapering is Coming – Avoid Zero CashFlow Stocks and Bonds, 10/14/21). This almost perfectly coincided with when I landed my first Wall Street position in January 1982.

Putting it mildly, the investment climate has changed dramatically over the last 4 decades. For better or worse, the investment world simply doesn’t behave or react to economic changes the way it used to. As an example:

Mountains of global debt coexist with lower (not higher) interest rates

Pervasive central bank intervention has generated investor moral hazard where frequently “bad news is good news”

Interest rates not only dropped to 0%, but actually went below zero as negativeyielding debt has proliferated around the world

These developments aren’t trivial – they have major implications for investors, redefining what role bonds can play in client portfolios. Read on for our current thoughts.

Over the years, I’ve witnessed the Fed’s role gradually shift from focused inflation fighter to inflation generator. Before 2008’s Great Financial Crisis, its primary focus was on its legal dual mandates of concurrently maintaining low inflation and fairly-low unemployment. If there was a bias, it was towards erring on the side of tamping down inflation through higher rates and allowing labor and financial markets to correct in response.

Since 2008, that philosophy’s given way to an increasing willingness to explicitly meddle with markets in an attempt to stimulate higher economic growth. The bias has instead shifted towards prioritizing full employment, even if at the cost of higher inflation. At the same time, the Fed has an unofficial “third” mandate of fostering financial market stability (the socalled “Bernanke doctrine”), which in practice has meant asset prices can’t be allowed to decline by inconveniently large percentages. Accomplishing this has required crossing several Rubicons that would have previously been unimaginable. In short, the investment climate has been turned upside down.

Taken at face value, this seems great for investors; having a central bank backstopping the market for over a decade has been tremendously profitable for asset owners. But there are two sides to this coin (like anything else in life), and the abundant market distortions from the moral hazard present a daunting challenge.

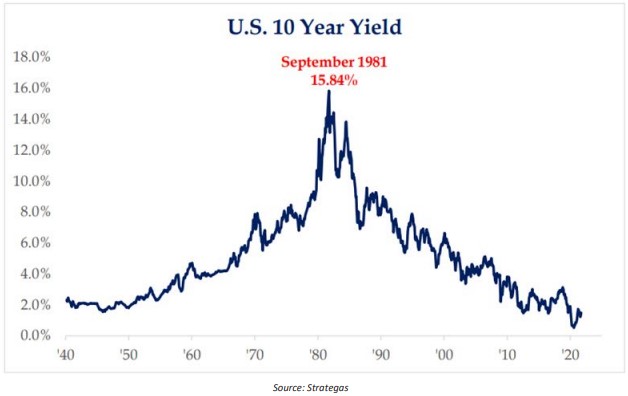

Prior to 2014, the modern investment world never experienced negative yielding debt. I never would have believed this would even be possible, let alone investors would position the safe portion of their portfolios in investments that will knowingly lose money. But in fact, when some major global central banks lowered their benchmark rates to negative, it caused bonds to have negative returns. Having peaked at over $18 trillion of global negative yielding debt in 2020, approximately $12.5 trillion of negative yielding debt exists today.

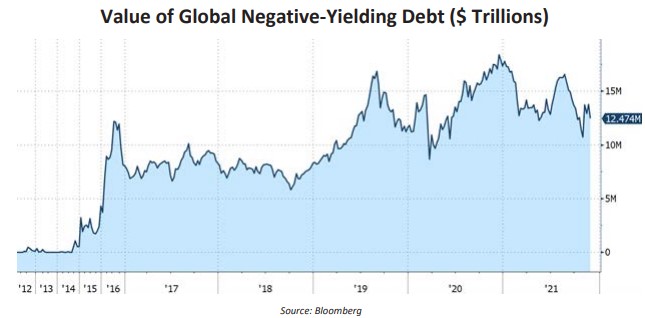

Negative-yielding debt is just the most obvious distortion – yields don’t need to be below zero to be fundamentally illogical. Closer to home, the fact that long-term 10-year Treasury yields now typically offer less than the rate of annual inflation (and that’s before taxes!) is a relatively new development that makes almost no sense and is something I haven’t experienced. It’s little comfort when riskless returns still can’t meet even this low of a bar.

This situation hasn’t arisen naturally; it’s a direct result of Fed intervention to artificially suppress the cost of capital and drive asset prices higher through multiple periods of direct purchases of US Treasuries and Mortgage-Backed Securities.

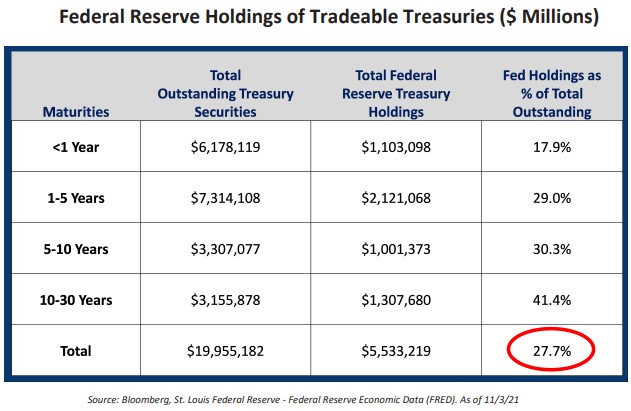

When the Fed first introduced Quantitative Easing (“QE”) in 2009 it was just a novel “short-term” program, but it’s since burgeoned into a massive market-shaping force, restricting Treasury supply to alter market pricing. In effect, we haven’t had a market-determined level of interest rates in over a decade. Today, the Fed owns over 27% of outstanding tradeable Treasury securities, and an even larger proportion of longer-term maturities. In times of true crisis (e.g. March/April 2020), the Fed has supplemented QE with even more radical forms of experimentation, such as direct purchases of corporate bonds and bond ETFs.

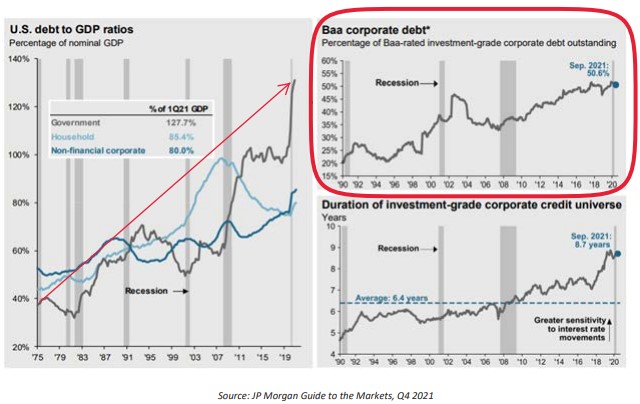

Of course, rational actors (including the federal government itself) have taken advantage of this nopenalties environment and drastically increased the amount of debt outstanding. Public and private debt outstanding has exploded, both in absolute terms and relative to the size of the overall economy (debt/GDP ratios). Further, corporate credit quality has declined, with just over 50% of investment-grade corporate debt now rated in the BBB range due to increased levels of leverage.

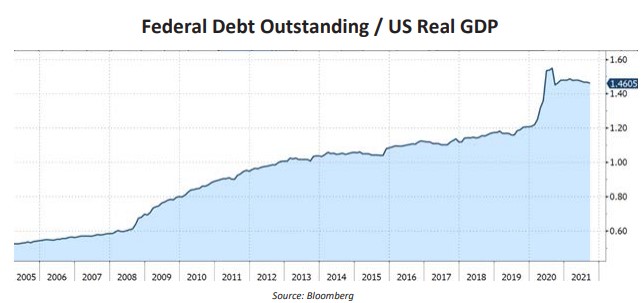

But one “law” of economics has held true – diminishing returns. All the added debt has bought less growth, with the ratio of federal debt to GDP heading continually higher (telling us the debt load is accelerating faster than underlying economic growth).

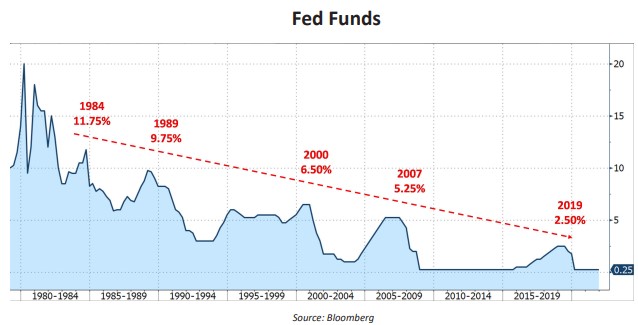

Ever since former Federal Reserve Chair Volcker successfully halted the double-digit inflation of the 1970s-80s, the Fed Funds rate has seen an unbroken pattern of lower highs and lower lows. As the chart below reflects, Fed Funds peaked at 20% in 1980. The next peak was 11.75% in 1984, followed by 9.75% in 1989, 6.50% in 2000, 5.25% in 2007, and 2.50% in 2019.

Can the pattern be broken this time? It’s difficult to imagine, given the potential consequences of rising debt service costs. Perhaps central bankers have unintentionally created a destructive dilemma: elevated debt loads weigh on growth and create a situation where higher rates would increase debt service costs and ultimately snuff out growth.

In the past, the value of including bonds in most clients’ asset allocations was easy to see. A properly constructed bond portfolio offered material interest income while prioritizing the safety of principal. For decades it was a win-win for client portfolios.

Today’s bond investors confront a seemingly no-win scenario: stay short and safe but earn almost nothing, or earn more by extending maturities and risk extreme price losses if rates tick even modestly higher. Since approximately June 2020, our view was (and continues to be) that the odds seem skewed towards ‘heads you win, tails I lose.’ As a result, we continue to allow portfolio durations to decline and limit reinvestments to shorter-term maturities, accepting the necessary consequence of low yields. “Ballast”-like bond positions like these can still offer investors a favorable combination of principal preservation and liquidity, and still play a role in most client asset allocations.

However, while our short-term positioning is clear, the daunting challenge will be portfolio positioning over the long term. Given the elevated debt levels and 40-year trend of lower highs in Fed funds rates, at some point, bond investors will be forced to accept longerterm rates that have historically been unattractive. Large amounts of Treasury supply will remain warehoused on the Fed’s balance sheet and unavailable to the market, while demand is poised to stay durably strong since our meager rates are still far better than the negative rates that dominate developed international markets. It’s simply not realistic to expect that the fixed income environment will revert to its pre-2008 levels anytime soon, and investors must adapt to this hard reality.

For many clients, this adaptation calls for reducing some of the traditional fixed income allocations and redirecting the proceeds towards other (potentially incomeoriented) investments. The rationale is simple; we simply see far better risk-reward profiles in some carefully-selected opportunities than what’s available in traditional public bond markets.

In January 2022, I’ll have the great pleasure of celebrating 40 years of following the markets. I still skip to work (well, most days it’s just down the steps to my home office, but close enough) with the same excitement as my first year in the business. Words don’t adequately express the gratitude I have for my Partners, Team and most of all, our clients who make this all happen.

As I look to the next 40 years, the only thing I can predict with total confidence is that we’ll experience many new challenges in the investment climate. I’m confident that our past experiences will prove critical in navigating whatever the future has in store. Over the coming months, look for similar “Reflections on 40 Years of Investing” white papers where I’ll draw on the lessons I’ve learned from past markets to think about how to prepare for what’s next.

Thanks for your support and the confidence you place in Treasury Partners. We’ll never squander that trust nor take it for granted. It’s truly an honor and a privilege to serve you, both for the past 40 years, and hopefully for the next 40!

Treasury Partners is a group of investment professionals registered with Hightower Securities, LLC, member FINRA and SIPC, and with Hightower Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor with the SEC. Securities are offered through Hightower Securities, LLC; advisory services are offered through Hightower Advisors, LLC. This is not an offer to buy or sell securities. No investment process is free of risk, and there is no guarantee that the investment process or the investment opportunities referenced herein will be profitable. Past perfor - mance is not indicative of current or future performance and is not a guarantee. The investment opportunities referenced herein may not be suitable for all investors. Yield and market values will fluctuate with changes in market conditions. Prices and availability are subject to market conditions. Projected cash flows will change as bonds mature. Some bonds may be called prior to maturity. The investment return and principal value of an investment security will fluctuate with market conditions so that, when redeemed, the value of the investment may be worth more or less than the original cost. The information herein has been obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but the accuracy of which cannot be guaranteed. Municipal bonds are subject to risks related to litigation, legislation, political changes, local business or economic conditions, conditions in underlying sectors, bankruptcy or other changes in the financial condition of the issuer, and/or the discontinuance of the taxation supporting the project or assets or the inability to collect revenues for the project or from the assets. They are also subject to credit risk, interest rate risk, call risk, lease obligations and tax risk. The market for municipal bonds may be less liquid than for taxable bonds. Income from some municipal bonds may be subject to the federal alternative minimum tax (AMT) for certain investors. Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. All data and information reference herein are from sources believed to be reliable. Any opinions, news, research, analyses, prices, or other information contained in this research is provided as general market commentary, it does not constitute investment advice. Treasury Partners and Hightower shall not in any way be liable for claims, and make no expressed or implied representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of the data and other information, or for statements or errors contained in or omissions from the obtained data and information referenced herein. The data and information are provided as of the date referenced. Such data and information are subject to change without notice. This document was created for informational purposes only; the opinions expressed are solely those of Treasury Partners and do not represent those of Hightower Advisors, LLC, or any of its affiliates.