Over the past few months, interest rates have surged from their post-Covid lows. One year ago, the 2-Year Treasury yielded a mere 0.15%; today, 2-Year Treasuries change hands at 2.75%. In that time, the Fed’s own dot plot increased its Q4 2023 Fed Funds expectation from 0% all the way to 2.75%.

This meteoric rise in rates and future expectations has led to heightened bond market volatility. In Q1 2022 the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index registered its worst quarterly performance in 40 years, losing 6% of its value. We alerted longtime readers to this risk last year on two occasions (Fed Tapering is Coming: Avoid Zero Cash-Flow Stocks and Bonds, 10/13/21, and 2021 Review and 2022 Outlook: Volatility Returns, 12/24/21).

Are we merely in the beginning stages of an aggressive inflation-induced tightening cycle not seen in 25 years? Or is this just a passing anomaly, after which we’ll revert to the lower post-Great Financial Crisis (“GFC”) rate regime? Read on for our updated thoughts.

The GFC was a generational turning point for fixed income investors. As you recall, following the GFC the Fed instituted unprecedented monetary policy actions, including a zero-interest rate policy (“ZIRP”) and Quantitative Easing (“QE”), to spur the economy. As recently as last summer, the Fed was explicitly operating under an “Average Inflation Targeting” framework, assuming several years of moderately >2% inflation was desirable to counterbalance the preceding decade of <2% inflation. The post-GFC rate environment has been dramatically different compared to the Volcker years when I was first cutting my chops on Wall Street. Well, as it turns out, the Fed certainly got its inflation (and plenty of it) in the end.

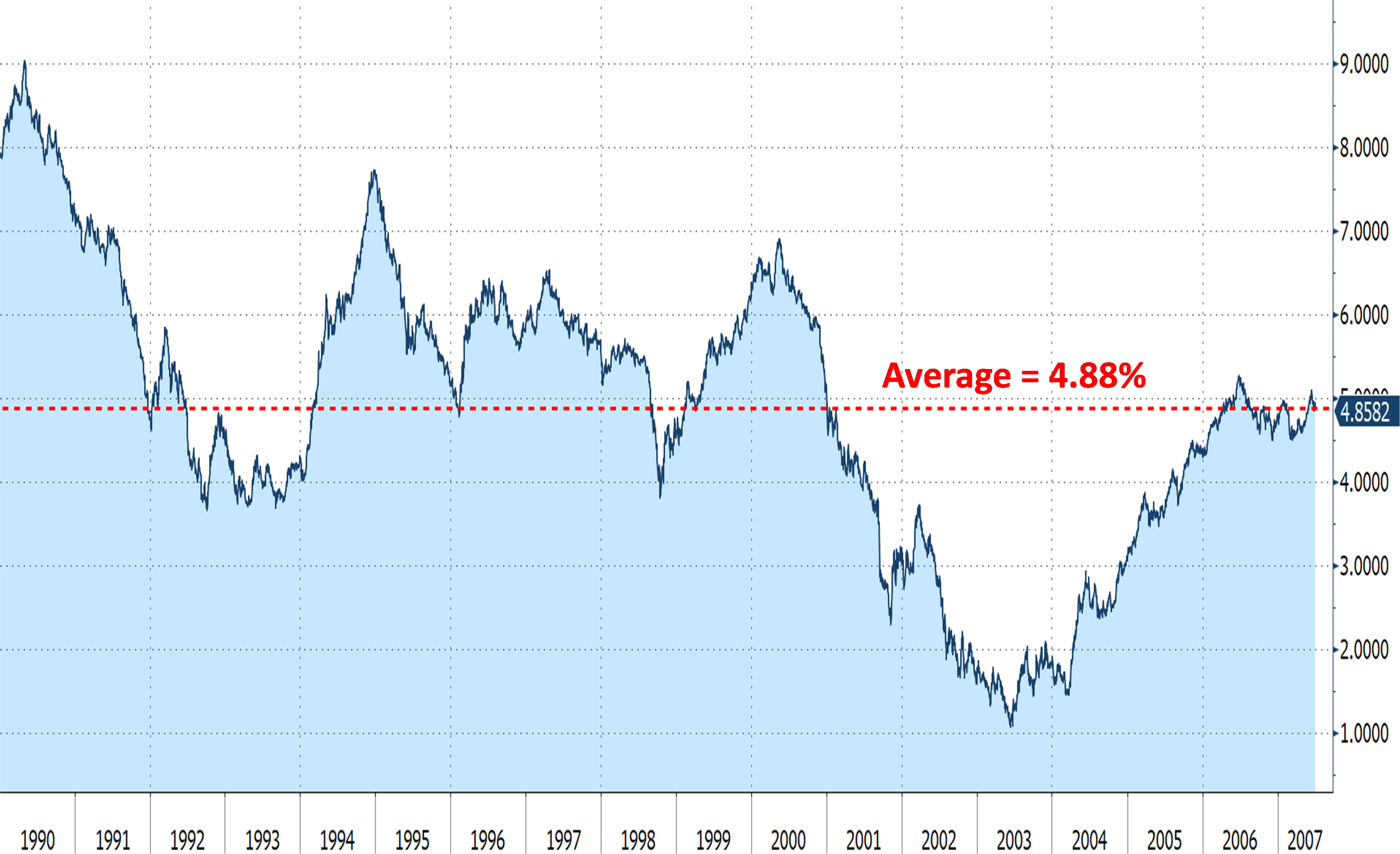

Let’s examine the differences between pre-and post-GFC rates for different Treasury maturities:

• From the 1990s leading up to the summer of 2007, the 2-Year Treasury averaged 4.88% while trading between a broad 1.00-8.00% range.

• Post-GFC, 2-Year Treasuries averaged a far lower 1.05% and traded almost exclusively within a narrow 0.10-3.00% range.

• From 1990 through mid-2007, the 5 Year Treasury averaged 5.43% while bouncing between a 2.00-8.00% range.

• After the GFC, it dropped to an average of just 1.72% and traded within a tight 0.25%-3.00% window.

• In the pre-GFC period, the 10-Year Treasury averaged 5.82% within a 3.00-9.00% range.

• Post GFC, the 10-Year Treasury averaged a mere 2.43%, never rising above 4.25% on the high end and scraping 0.50% on the low end (in fact, it spent almost all of 2020 below 1.00%!).

There are strong arguments that rates are primed to keep soaring:

• War-induced inflation continues to rage; both headline CPI and core PCE are consistently printing well above the Fed’s stated 2% target. The Fed is clearly late to the party.

• The strength of the labor market provides cover for aggressive tightening, with the unemployment rate practically at its 30-year low.

The Biggest Decision Facing Bondholders Today

However, the rationale for Treasury yields holding the line at or near 3.00% is also compelling:

• With Quantitative Tightening (“QT”), the Fed has another powerful (albeit novel and untested) tool that can be used to withdraw market liquidity and act as a substitute for Fed Funds rate increases.

• Bound by its dual mandate to both fight inflation and promote high employment, the Fed faces a delicate balancing act. Inflation is unlikely to be fully tamed without substantially higher rates but tightening too fast risks breaking labor markets and precipitating a recession

With all these intermingled variables and dueling objectives, how should investors position bond portfolios?

In the shorter-term maturity ranges, the market has already priced in a rapid pace of rate hikes. The 6-Month Treasury currently yields 1.34%. 6 months from now, the new 6-Month Treasury would have to yield at least 2.78% for an investor to break even compared to simply buying and holding today’s 1-Year Treasury at 2.06%. For context, in the 15 years since the GFC, the 1-Year Treasury has spent less than 1-Year trading above 2.25%. The curve is steep and reflects aggressive Fed action.

• Conclusion: Investors with 1-year mandates should extend maturities

Similarly, the 1-Year Treasury, 1 year from now would have to yield at least 3.44% for an investor to break even compared to investing in today’s 2-Year Treasury at 2.75%

• Conclusion: Investors with 2-year mandates should extend maturities

In summary, short-term rates already reflect aggressive Fed tightening. By extending into 1- or 2- year debt, corporate cash investors can simultaneously lock in both the steep slope of the curve while benefitting from the protection of future “roll-down”. By roll-down, we mean the natural process whereby bonds purchased today eventually ‘season’ into shorter-maturity holdings while retaining the same book yield (e.g., holders of today’s 2.75% 2-Year Treasury will, in a year, be holding what will have become a 1-year maturity with that same 2.75% purchase yield, priced accordingly by the market). This automatic process of seasoned positions ‘rolling down the yield curve’ offers a degree of natural protection against rising rates.

Just as important, remember that while the risk of rates returning to pre-GFC levels will always exist, current rates are very attractive compared to more recent post-GFC levels. The potential reward for waiting to extend is small, especially if this turns out to be the moment of “peak hawkishness.”

The 5-Year Treasury has been trading at or slightly above the same yield as the 10-Year maturity, with levels available today attractive compared to post-GFC averages but unappealing by pre-GFC standards.

Currently, high-grade corporate debt with 5-year maturities is available at 3.50%+ yields. In our decades of experience, that’s historically been an attractive rate of return for risk-averse corporate investors. Roll-down remains a factor in this part of the curve; if an investor locks in a 3.50% 5-year position today and rates rise 1.00% over the next year, the bond ‘rolls down’ into a 3.50% 4-year position which may reflect the then-current market levels, depending on the slope of the curve.

Investors with established bond ladders are particularly well-suited to take advantage of this strategy. The nature of ladders takes full advantage of roll-down benefits, while also providing a steady stream of ongoing liquidity. If rates continue to rise, natural maturities can always be reinvested into higher-yielding positions.

• Conclusion: Investors with laddered portfolios should extend maturities, as the potential for further rate increases is offset by ongoing liquidity and rolldown protection.

Although 10-Year Treasury yields have certainly improved, given the possibility of large price swings (from a given change in rates), the risks of extending now remain elevated. Today’s levels look attractive relative to post-GFC rates but come up very short relative to pre-GFC norms, when inflation was a significant factor.

Unlike shorter-term maturities that can benefit from significant offsetting protection via rolling- down in maturity length, the effect is much diluted in longer-term bonds. Whereas shorter-term maturities can rely on ‘coupon protection’ to help offset price changes, this is greatly diminished with longer term maturities. As a result, further rate increases will have a disproportionately magnified impact on longer-term bond prices.

For example, investors who bought the 10-Year Treasury 6 months ago at approximately 1.55% now face a nearly 11% unrealized price loss: no amount of roll-down into the 9.5-year portion of the curve can meaningfully offset this price decline.

• Conclusion: Investors with longer-term mandates shouldn’t broadly extend maturities given the risk of inflation, rising rates, lack of roll-down protection, and the uncomfortably large gap between pre- and post-GFC rates. That said, there are exceptions worth considering. We’re currently finding attractive opportunities in the municipal bond market: 10-Year AAA-rated municipals which were yielding 60% of their equivalent maturity Treasuries a year ago are trading at 90% today. In select instances, high grade municipals callable within the next 5 years are available at 3%+ tax-exempt yields. These levels are attractive by any standard.

This Alert has focused on highlighting the stark differences between pre- and post-GFC yields. Across the curve, rates are now testing post-GFC highs that barely qualify as pre-GFC lows. One paradigm indicates this is an attractive top, while the other warns it’s just the beginning of a secular rise in rates. Deciding on direction is the single biggest decision facing bondholders today.

Right now, the risk/reward ratio is favorable in short and intermediate-term bonds vs. the long end, which is why we’re extending maturities in the former but not in the latter.

We thank you for the trust and confidence you place in us during these challenging times. Feel free to reach out to us for any additional discussion.

Treasury Partners is a group of investment professionals registered with Hightower Securities, LLC, member FINRA and SIPC, and with Hightower Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor with the SEC. Securities are offered through Hightower Securities, LLC; advisory services are offered through Hightower Advisors, LLC. This is not an offer to buy or sell securities. No investment process is free of risk, and there is no guarantee that the investment process or the investment opportunities referenced herein will be profitable. Past perfor - mance is not indicative of current or future performance and is not a guarantee. The investment opportunities referenced herein may not be suitable for all investors. Yield and market values will fluctuate with changes in market conditions. Prices and availability are subject to market conditions. Projected cash flows will change as bonds mature. Some bonds may be called prior to maturity. The investment return and principal value of an investment security will fluctuate with market conditions so that, when redeemed, the value of the investment may be worth more or less than the original cost. The information herein has been obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but the accuracy of which cannot be guaranteed. Municipal bonds are subject to risks related to litigation, legislation, political changes, local business or economic conditions, conditions in underlying sectors, bankruptcy or other changes in the financial condition of the issuer, and/or the discontinuance of the taxation supporting the project or assets or the inability to collect revenues for the project or from the assets. They are also subject to credit risk, interest rate risk, call risk, lease obligations and tax risk. The market for municipal bonds may be less liquid than for taxable bonds. Income from some municipal bonds may be subject to the federal alternative minimum tax (AMT) for certain investors. Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. All data and information reference herein are from sources believed to be reliable. Any opinions, news, research, analyses, prices, or other information contained in this research is provided as general market commentary, it does not constitute investment advice. Treasury Partners and Hightower shall not in any way be liable for claims, and make no expressed or implied representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of the data and other information, or for statements or errors contained in or omissions from the obtained data and information referenced herein. The data and information are provided as of the date referenced. Such data and information are subject to change without notice. This document was created for informational purposes only; the opinions expressed are solely those of Treasury Partners and do not represent those of Hightower Advisors, LLC, or any of its affiliates.