Investors have had to endure a rough ride this year. Markets entered 2025 optimistic about the incoming presidential administration and frontloaded expectations for the 'sweets' (favorable tax legislation, deregulation) before the 'indigestion' (additional tariffs, reduced government spending). But thus far, Trump 2.0 has resulted in plenty of market indigestion, are 'sweets' still on the menu going forward?

We have all had to process many 'fuses' being lit in a short period of time, and emotions are running high for many. But as professional investors, it's our job to try and filter the signal from the noise. In this Alert, we'll briefly outline our current thinking on the potential positives and negatives from President Trump's policies while outlining the key 'pivot points' to monitor. We will focus on issues which could affect the size of the federal budget deficit and the growing Treasury debt load, two interlinked concerns that help fuel the significant volatility in equity and fixed income markets.

Here is a far-from-exhaustive list of possible market-benefitting developments to watch for:

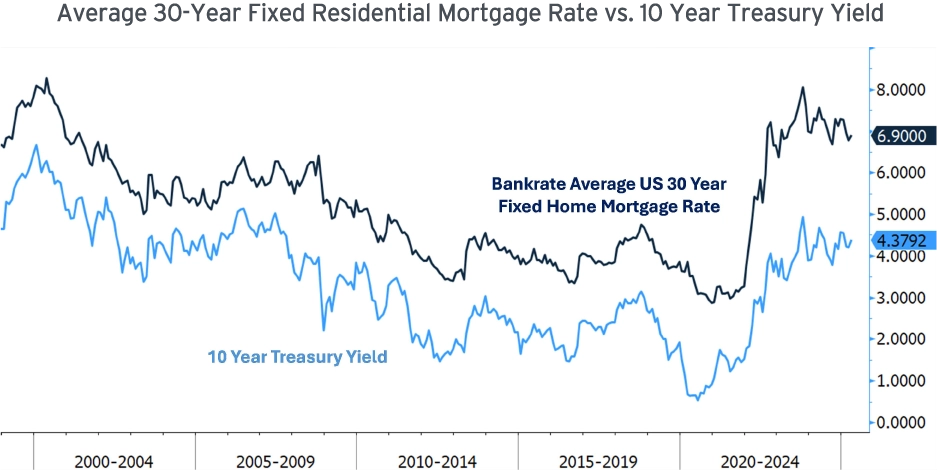

A smaller federal government would mean less federal spending, and if the current administration is successful in reducing both the federal deficit and the cost of long-term federal borrowing (the latter of which is a stated target of Treasury Secretary Bessent), that would lead to lower Treasury issuance and federal borrowing costs.

Since the rates on Treasuries serve as the base reference rates for essentially all financial and credit assets, lower government bond yields would translate into lower financing costs across the economy (think mortgages, corporate, and municipal bonds).

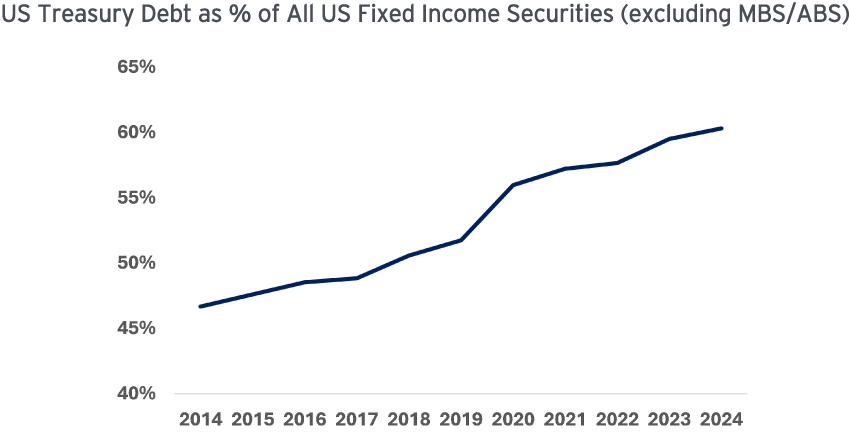

Lower Treasury issuance would also lead to less 'crowding out' of credit markets, as less investor capital would need to be dedicated to financing the federal government's borrowing needs and could instead be redirected to support the private sector. This is a growing concern, as the proportion of Treasury debt within the domestic fixed income market has ballooned in recent years.

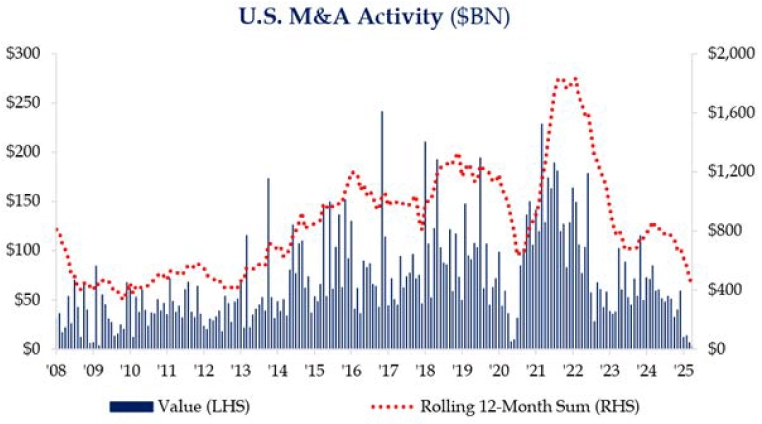

A lower and less heavy-handed regulatory burden promises to unleash economic 'animal spirits', and active deregulation could be particularly beneficial for certain industries (e.g.: banking, oil/gas, etc.). With domestic merger and acquisition (M&A) activity clearly waning, such measures could help boost this important driver of economic renewal and vitality.

If the new tariff regime and/or newly adopted tax incentives succeed in materially increasing 'onshore' manufacturing back to the US, it would help revitalize both domestic labor markets and productive capacity.

On the other side of the ledger, here are the most salient policy-related risks we're monitoring:

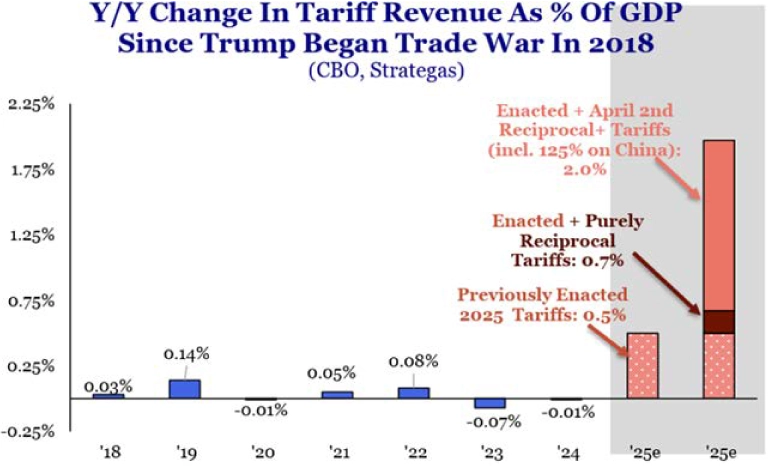

The newly announced tariffs are significantly higher compared to those established during the Trump 1.0 and Biden administrations. Although this represents a welcome source of substantial new and recurring revenue for the federal government, tariffs are effectively the same as a major tax increase on domestic consumption, generating the classic negative economic consequences that come with any tax hike.

Additionally, there remains the potential for retaliatory action from our trading partners. Foreign private institutions and individuals could also strike back in their own manner, as there is already evidence that international capital allocators have begun reducing their exposures to US financial markets and US dollar-denominated securities on the margins.

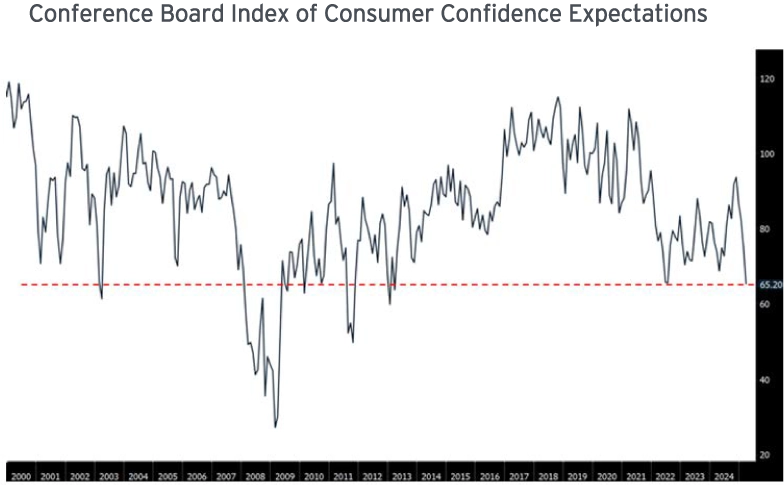

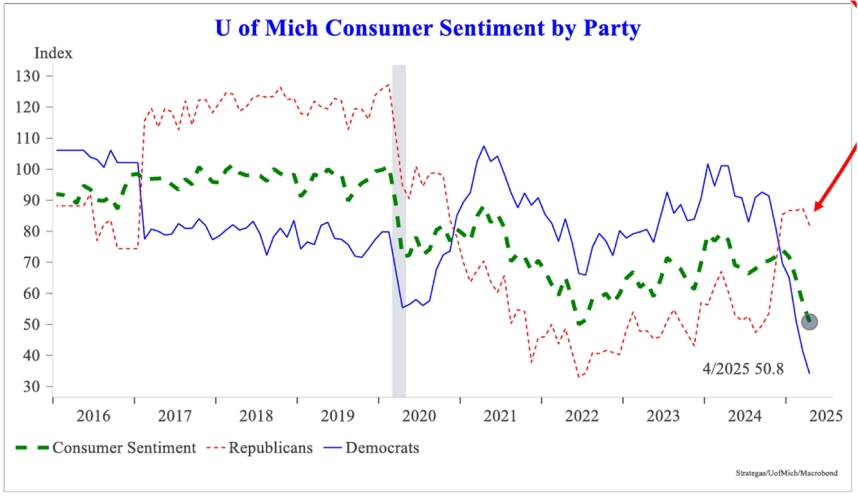

The erratic manner in which tariff policies were rolled out and subsequently modified has eroded confidence. Consumers' expectations of economic conditions have dropped significantly and are now plumbing depths rarely seen since 2008's Great Financial Crisis.

As an aside, it pays to take consumer confidence surveys with a healthy grain of salt. They are strongly correlated to their respondents' political preferences, which raises the question of whether this data is ultimately useful for economic forecasting.

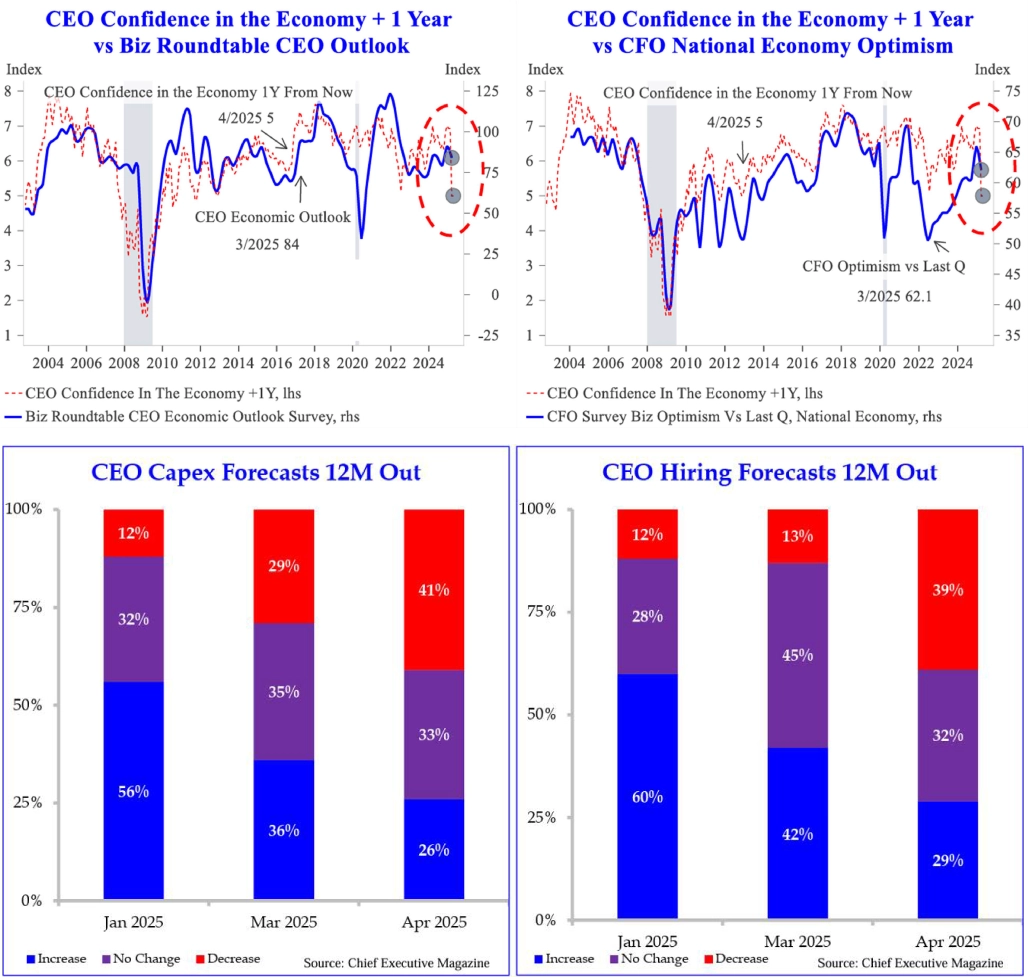

Surveys of business executives' confidence do not necessarily suffer from this same shortcoming. Unfortunately, the current messaging from these indicators also matches consumers' sour mood.

The Department of Government Efficiency's (DOGE) layoffs of federal workers could weigh on the labor market (particularly in certain geographic areas). Although this could cause the unemployment rate to climb, timely labor market indicators such as weekly jobless claims are not yet reflecting any deterioration.

The Federal Reserve appears increasingly stuck between a rock and a hard place, with a slowing economy but stalling (possibly even reversing) progress on inflation bringing the two aspects of their dual mandate into tension. Additional pressure in the form of threats to the independence of monetary policy aren't likely to help successfully resolve this dilemma.

We're closely watching what happens with respect to the following three interlinked issues, as their resolutions over the coming months will have widespread consequences. However, as discussions and negotiations on these topics are currently very fluid, it's still too soon to tell in which direction they are trending.

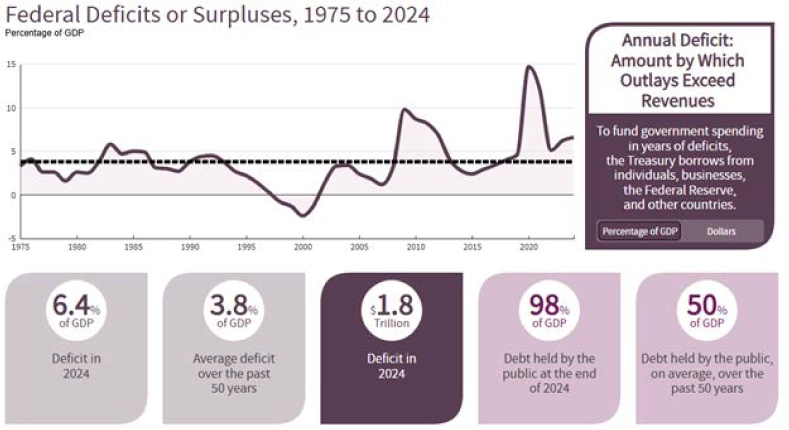

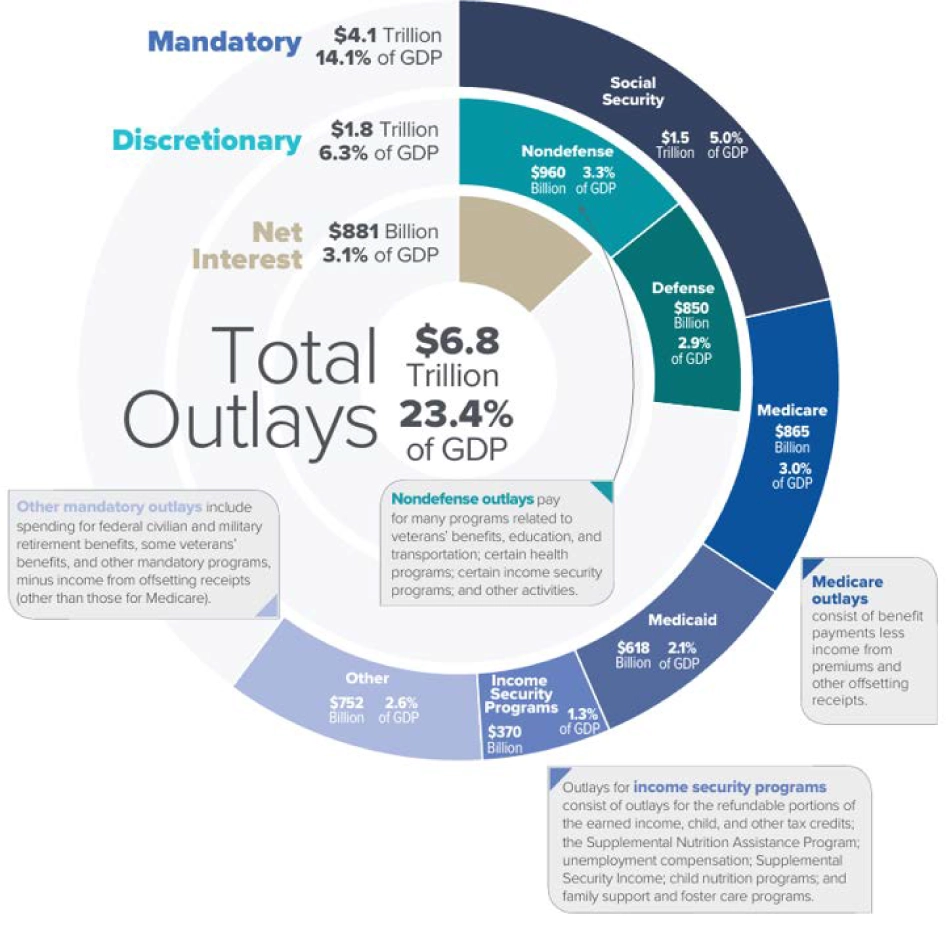

Size of Federal deficit. It's a simple fact that the federal government's budget deficit has been moving in the wrong direction for decades and has now reached an unsustainably high level.

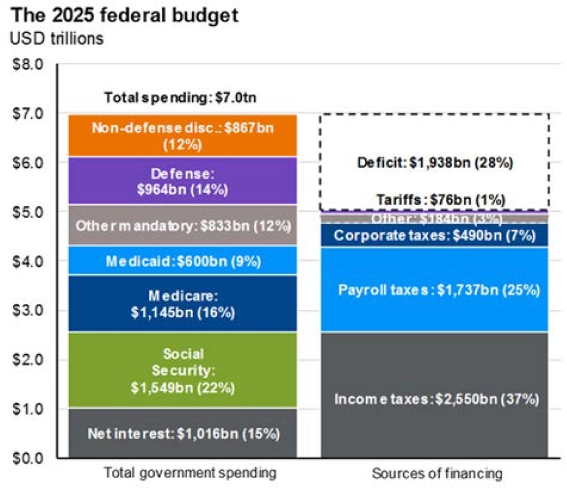

The budget deficit is a product of federal spending outpacing revenues; therefore, the only mechanisms to reduce it involve increasing revenues, decreasing expenses, or some combination of both. Given that appr. $1 goes out the door for every $0.72 of revenue that comes in, this is a large and difficult puzzle to solve. Any solution undoubtedly involves tough decisions.

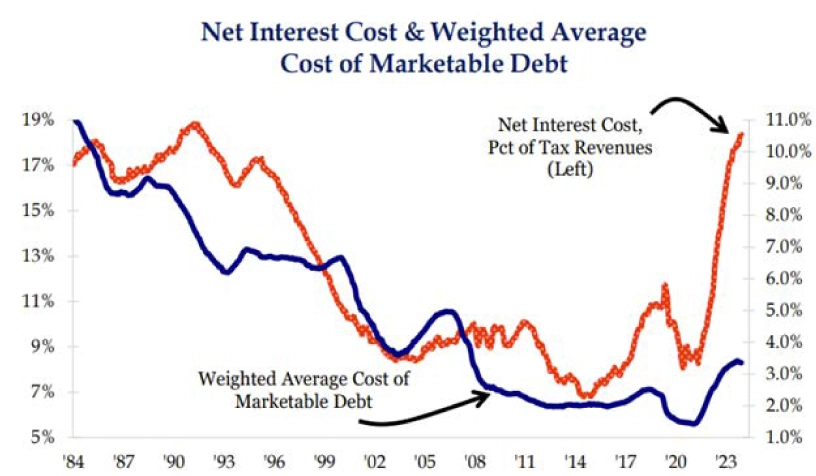

Cost of Federal Borrowing. The cost of servicing Treasury debt is an increasingly large problem, with net interest payments recently surpassing defense spending.

Moreover, the cost of servicing Washington DC's bloated debt stack probably won't decline anytime soon. It's more likely to keep rising further, as we print trillions in net new Treasuries while the maturing bonds from the past 15 years' worth of ultralow interest rates are steadily refinanced at today's higher rates (which themselves are not that high by historical standards). The problem is only getting worse.

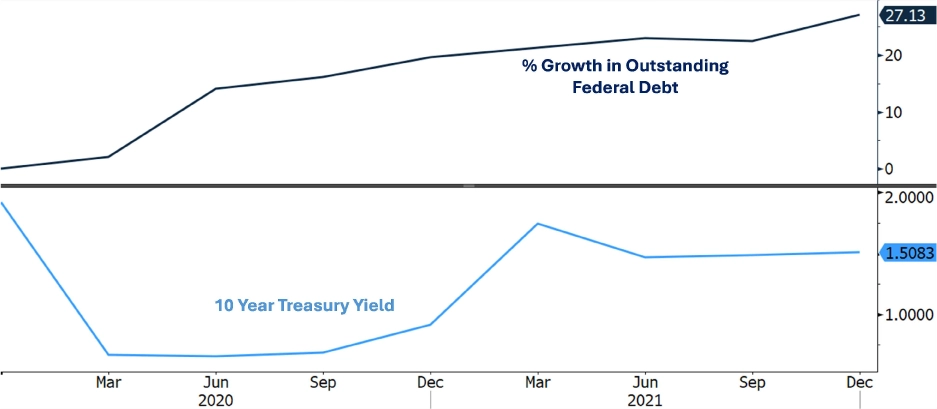

Higher deficits lead to more Treasury issuance, and although a higher federal debt load doesn't always immediately translate into higher borrowing rates (see 2020-2022), in the long run it is undeniably a major determinant.

Every additional budgetary dollar that needs to be devoted to debt service is a dollar that can't be spent elsewhere, and this dynamic could force unpopular choices by 'crowding out' spending for competing governmental initiatives.

From a political perspective, it's not easy to figure this problem out; there's a reason the can has been kicked down the road over the past several decades. But make no mistake - we're running out of road.

Changes in Tax Policy. President Trump originally campaigned on a platform of extending the lower individual and corporate income tax rates that are slated to expire at the end of 2025. Moreover, although additional 'sweeteners' were also floated (e.g. no taxes on tip income, no taxes on Social Security benefits, etc.), new income in the form of added tariffs - a tax on domestic consumption - has now been added to the federal revenue mix. The magnitude of each of these changes is anybody's guess, and a moving target as the economic backdrop evolves. Washington DC's budgetary picture is in greater flux than we have seen in many years

Changes in tax law will affect the size of the federal deficit, as will shifts in the federal government's cost of borrowing. Increases in the projected size of the deficit could lead markets to demand higher Treasury rates, and vice versa, which could scramble the math that's informing the tax law negotiations and make things even more difficult than they already are. Chicken, meet egg.

One thing is clear to us: market volatility is here to stay as investors continue to pay close attention to every new headline. Much of the current upheaval has been driven by executive decisions personally made by President Trump, with little Congressional action to date. To the extent that this continues, both policies and market reactions will continue to be subject to sudden and dramatic reversals going forward.

The fact that domestic equity markets entered the year with elevated Price/Earnings multiples didn't leave much margin for error. Part of the indigestion we've experienced thus far is simply an inevitable adjustment away from a frothy environment.

But something we think gets lost in the day-to-day drama is that everything about President Trump's history suggests that he embraces a purely transactional approach to most affairs. Although everything is subject to negotiations that can be hard-fought, the end game always involves concluding with a 'deal' of some sort and moving on. We're publishing this Alert as the new administration concludes its first 100 days in power: that's just over 6% of the President's 4 year term in office. It's still early, and we think what we've seen so far has been the opening salvo of the 'negotiation' phase, with the resulting market volatility both a reaction and an acknowledgment that we've yet to reach the true 'deal-making' phase.

Negotiators from all sides still have thorny issues to iron out. For example, the European Union currently imposes a 10% tariff on imported American cars, higher than the US's 2.5% blanket tariff on imported EU autos but also lower than our specific 25% tariff on imported pickup trucks (it's not a coincidence that pickup trucks are American automakers' most important sources of profits). Will the ultimate resolution see the EU's tariffs move lower, the US's tariffs move higher, or additional new carveouts come into play? The economy and markets can adjust to any of these scenarios, but the problem right now is the uncertainty.

Our base case is that we are now moving into that key 'deal-making' phase which should provide clarification and resolution on these critical issues. We expect that market anxiety should improve significantly once the uncertainty gets reduced to more manageable levels, as companies and individuals will be able to start taking the steps needed to adjust to whatever the new reality looks like. We expect substantial progress on trade deals with most countries by the end of Q3, with formal negotiations with our major trading partners - China, Mexico, Canada, and the EU - commencing by the end of 2025 or the start of Q1 2026. Substantive movement towards reaching resolutions should herald a return to a more 'normal' (read: less volatile) day-to-day investing environment. Any progress in terms of delivering on hoped-for 'sweets' - such as favorable tax policy or concrete signs of deregulation - would boost this dynamic.

In the meantime, the real economy will not simply stand still - we're closely monitoring the data for signs the environment is shifting. It has been apparent for some time now that the economy is slowing, but the important questions for markets are how much and how fast? There are certainly some indications of emerging weakness: low and still-falling consumer and business sentiment surveys, plateauing inflationary data, and increasingly cautious corporate earnings outlooks, to name a few. At the same time, there are also signs of ongoing resilience: labor markets are holding up well, consumer spending remains solid, and the Q1 2025 corporate earnings reported thus far have been acceptable (albeit paired with less-than-optimistic forward guidance). While the reasons for maintaining vigilance are growing, it appears a recession can still be avoided - this outcome would obviously be good for stock valuations. At this time, we don't anticipate a recession in the near term, though this will largely be determined by developments in major trade negotiations.

Investors currently underweight their target equity allocations should consider gradually adding to stocks to rebalance back closer to target. Conversely, those clients who are currently overweight equities and aren't comfortable with their exposure to price volatility ought to take advantage of market rallies to reduce positions and raise cash to redeploy elsewhere (e.g. into long-term municipal bonds). Remember: as longterm investors, we're managing wealth with the goal of compounding it over the next 5-10+ years, not just the next 5-10 months. Stay focused on the long-run, not just the latest data print or news headline.

Finally, we note there are many doomsayers out there predicting the downfall of American financial dominance. To be clear: we're not concerned about the US dollar losing its status as the world's only true reserve currency, nor do we see a mass exodus of foreign investors out of their holdings of US Treasuries and securities. While reduced American trade deficits would certainly result in fewer foreign holdings of US dollars being recycled back into US financial assets, there is simply no realistic alternative to the US dollar's unique position as the preferred currency of global trade. For that matter, there are no alternative capital markets that are realistically close to being as deep, liquid, and robust as ours. Although foreign institutions and individuals may choose to reallocate a larger degree of their risk exposures into non-USD securities going forward, the impact is likely to be muted over the long run.

As always, please reach out to us if you have any questions.