The current year has already proven to be highly volatile, as rapidly shifting geopolitical developments collide with economic fundamentals and corporate earnings that typically evolve at a much slower pace.

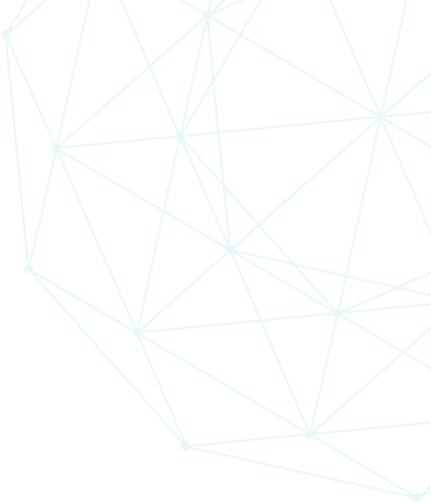

Equities in particular have been on a roller coaster. The S&P 500 came very close to entering a bear market on April 8th (troughing at -19% from the preceding peak), and then quickly rallied nearly 25% from those lows to reach fresh all-time highs and post a modest +5% YTD gain. Talk about a wild ride!

The primary impetus for both the selloff and subsequent recovery was policy driven. President Trump's April 2nd "Liberation Day" announcement establishing worse-than-expected import tariffs severely damaged investor sentiment. Only after the onerous tariffs were 'paused' was the impressive bounce-back able to take hold.

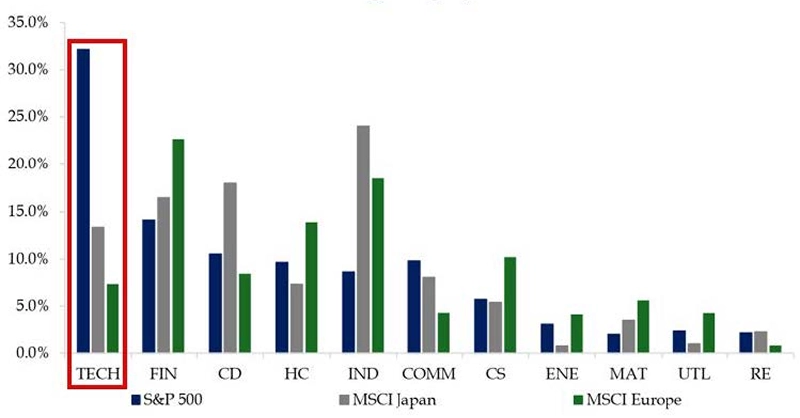

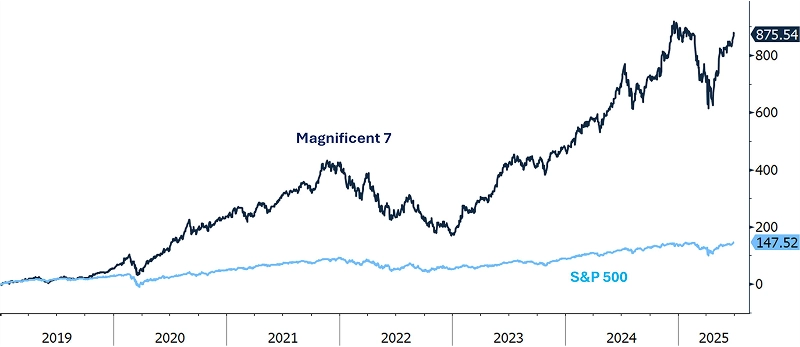

The Q2 rally was truly one for the history books with large-cap tech leading all other sectors with astounding +30 to 40% gains over less than 60 trading days.

Meanwhile, international equities are the undisputed year-to-date stars, posting stellar returns through the halfway point. However, while their 2025 YTD performance has been favorable, over longer time frames non-US equity returns have been dwarfed by their domestic counterparts.

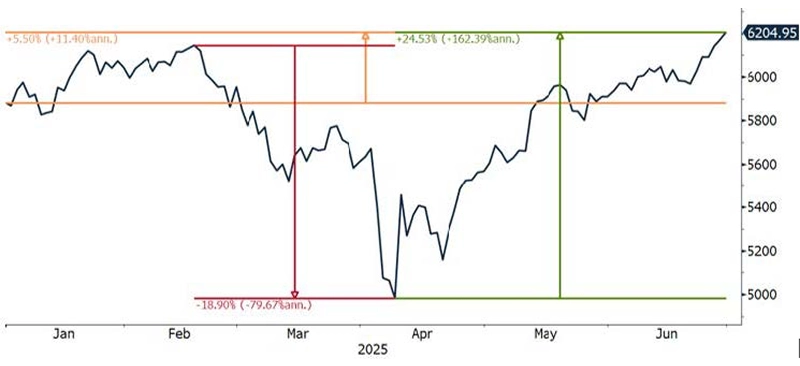

Furthermore, for each of these indices at least half of the YTD international outperformance can be directly attributed to the impact of a declining dollar, which has rapidly fallen to its weakest levels in several years.

This is a great opportunity to remind readers that this volatile environment is emblematic of why we focus so intently on customizing asset allocations for long-term capital appreciation. The quick and unexpected policy reversal of the original "Liberation Day" tariffs followed by the subsequent surge in the S&P 500 to fresh all-time highs could never have been predicted. Time in the market, not trying to time the market, is how wealth is ultimately compounded.

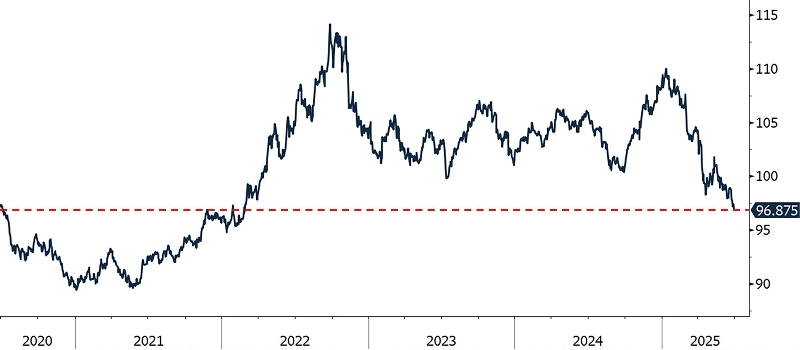

Developments in fixed income markets were no less interesting, challenging the conventional wisdom that a tariff-induced inflation spike was imminent and would force rates higher in response.

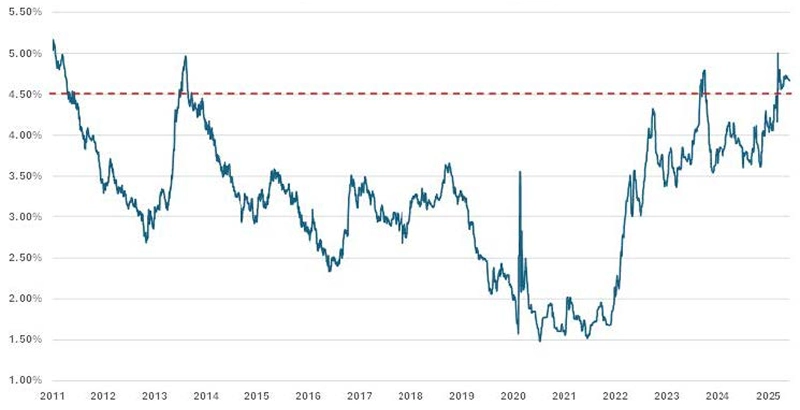

Although the 10 year Treasury yield climbed to 4.80% in January/February on those concerns, when the feared uptick in inflation ultimately didn't materialize rates subsequently declined to trade within a tight 4.00-4.50% band. The 10-year Treasury is currently yielding right around 4.25%. Similarly, the 2 year Treasury yield that started the year as high as 4.60% is now at 3.70%, at the lower end of its own entrenched 3.75-4.00% trading range. As clients know, we've been doggedly extending maturity profiles within bond portfolios all year, clearly disagreeing with tariff-induced inflation thesis.

Overall, the economic data continues to reflect an environment of sustained growth: jobs and employment numbers are positive, inflation is trending lower (despite tariff-related headwinds), and the tariffs themselves have delivered only a glancing blow to corporate earnings forecasts.

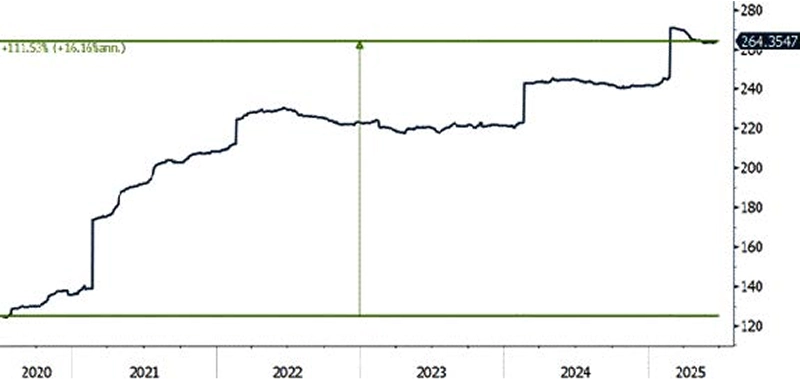

It's truly remarkable how well the US economic engine has taken everything in stride, and in particular how well corporate profitability has held up. In just 5 short years corporate America has managed to more than double its Earnings Per Share numbers while navigating a tsunami of challenges - a global pandemic, a rapid 500 basis point increase in borrowing rates, broad and material new tariffs, etc.

Lately we feel like our 'traditional' style of analysis - i.e. evaluating core fundamental indicators such as economic statistics, Fed forecasting, etc. - has taken a back seat to the latest news out of Washington.

Monitoring all the sweeping policy changes has become a vitally important component of any serious investment process. The day-to-day changes in policy can and have resulted in significant impacts for specific sectors and individual companies alike. In effect, we’re navigating a policy environment where anything and everything is on the table.

As an example, although the tariffs haven't resulted in the economic hammer-blow many had originally anticipated, it's important to remember that many of the worst impacts have simply been on 'pause.' Lets not forget the 'pause' is scheduled to expire on July 9th and could catalyze renewed market volatility. We're keeping close tabs.

A side effect of all the focus on Trump is a bull market in overwrought handwringing. One such worry that's very popular is the fear that American 'exceptionalism' - our innovation-driven economic growth and commensurate best-in-class financial market returns - is coming to an end.

This strikes us as ridiculously blown out of proportion. Simply put, the US's preeminent position as the leader of cutting-edge technological innovation and growth isn't going away just because half the world is uncomfortable with Trump's policies and public persona. Any investor seeking significant exposure to innovation, and the attractive growth prospects it fosters, has no choice but to participate in American markets.

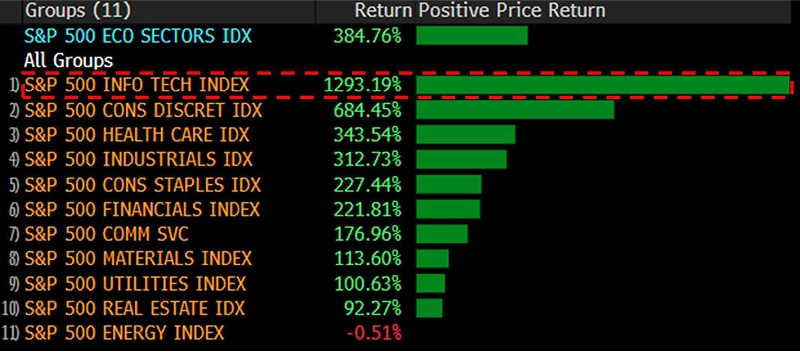

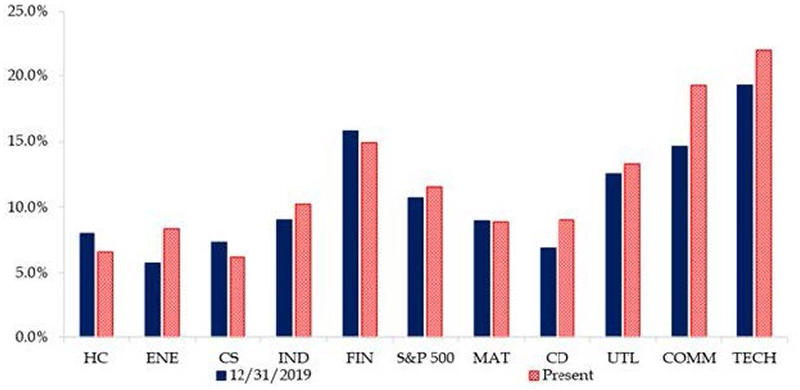

This is a critical point: exposure to the US tech sector has been the undisputed driver of the overall equity market's growth (and, in turn, American equity outperformance vs. the rest of the world) since 2008's Great Financial Crisis.

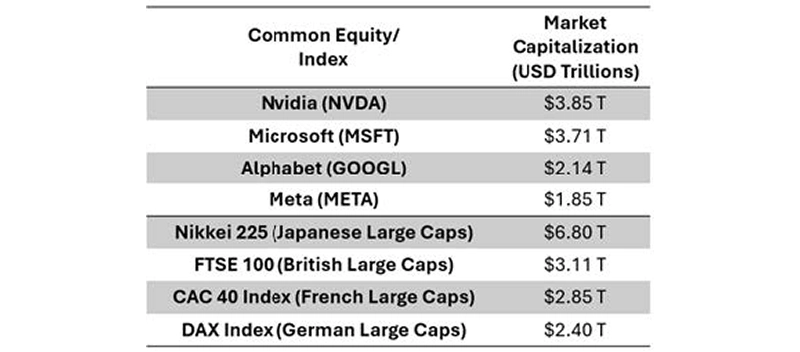

Moreover, the American dollar is still the world's only reserve currency and the undisputed medium of global trade in goods and major commodities. This is a powerful advantage and it's a key reason why US dollar-denominated financial markets are the deepest and most liquid in the world. It's not particularly close either - there's simply no other viable large-scale alternative that can match the robust opportunities and scalable size of our markets. Case in point: several US large-cap tech companies boast market capitalizations comparable to the entire equity markets of some G7 economies!

For these reasons and more, we don't see any potential for widespread capital flight away from US dollar-denominated assets and markets. For large asset managers throughout the world seeking long-term capital appreciation, a heavy allocation to the American economic growth engine is non-negotiable.

By essentially all conventional measures of valuation, domestic stock markets are expensive. At current levels, the S&P 500 price/earnings ratio pencils out to >23x consensus 2025 earnings estimates (and >20x 2026 forward estimates of $300/share) – talk about priced to perfection!

The problem with such rich valuations is that it increases the market's fragility - the good news is not only priced in, but it also needs to keep coming consistently. An outright bullish investor would have to believe in continued earnings growth and, in particular, no slowdown whatsoever of the growth rates of the large-cap tech companies that dominate the S&P 500's overall returns. Moreover, there's little leeway to absorb any bad news (and in the real world, there's always at least some bad news). With all the plentiful sources of potential volatility we've discussed in this Outlook, that strikes us as...unlikely, at best.

I'm often asked how I can be comfortable owning stocks at 20x+ earnings when earlier in my career (say, 20-30 years ago) a 16x multiple was considered expensive. Consider this scenario: if we assume the 2025 and 2026 consensus EPS estimates of $264 and $300 are correct, and further assume 5% growth in 2027's numbers, then today's S&P 500 at 6,200 and 2027's appr. $315/share earnings drops the market multiple back below 20x. To be clear, that's a lot of optimistic ifs - but with the way corporate America has navigated this volatile year, they've earned some benefit of the doubt.

But all that being said, I just don’t believe in relying upon broad market multiples as a guidepost for investing, especially when we can focus on finding pockets of rising cash flows and clear business momentum. A rich market in the aggregate doesn't mean there aren't sources of opportunity to be found within specific sectors and companies, and we continue to see the most compelling in the same place we've found it over the past several years - large-cap tech.

All the reasons we've discussed in white papers and portfolio reviews over the years still apply today, nor do we see them changing materially anytime soon:

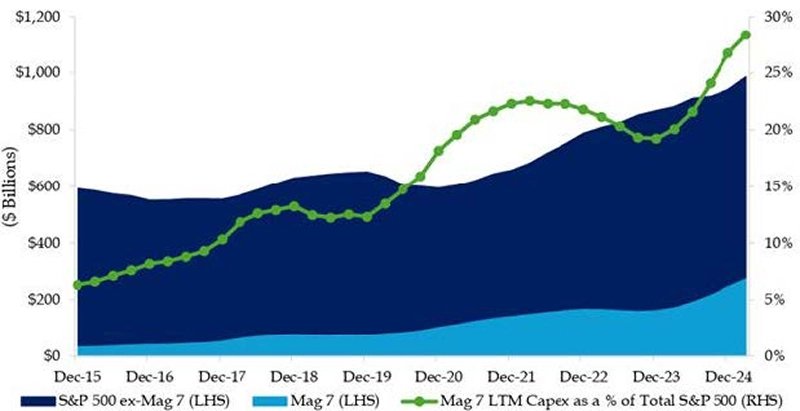

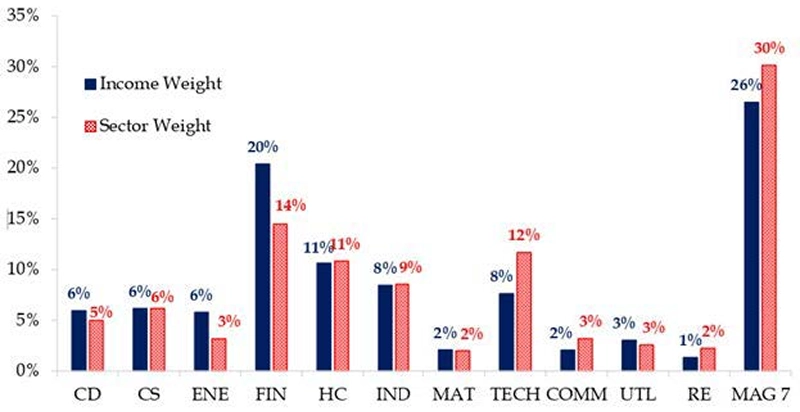

Large-cap tech companies don't just earn money - they consistently run circles around all other sectors.

Moreover, large-cap tech (whose constituents are split between the Information Technology and Communications Services sector classifications) are actually managing to grow their market-leading margins even further.

These companies aren't resting on their laurels - far from it, they're pouring essentially all their free cash flow generation back into their businesses, reinvesting via heavy capex expenditures that should create even more future value.

It's a powerful set of arguments, and we're still convinced. However, we admit our call isn't exactly an out-of-consensus strategy, as large-cap tech already comprises more than a third of the value of the entire S&P 500 and has driven outperformance for several years running.

But we're focused on the reason why it's gotten to that point - it's still the prime source of earnings growth both today (by a large margin to boot) and likely tomorrow (as it has upside benefits from the AI revolution). This justifies a premium valuation for above-average growth, and one thing I've come to appreciate with age is that often, real long-term capital appreciation doesn't come cheap - particularly when there's a scarcity factor due to the very limited number of genuinely remarkable companies.

As an aside - we sometimes still run across comparisons of today's environment to the Dot-Com Bubble of the late 1990s. This analysis misses the forest for the trees. At the height, it is true that the S&P 500 of that era traded at >24x forward earnings estimates - but the key difference is that the hyped-up companies driving the market's returns in 1998-99 were unprofitable cash burners. Notwithstanding the fact that both eras were characterized by their tech sectors, it's difficult to imagine a more different set of circumstances when looking at the details that matter.

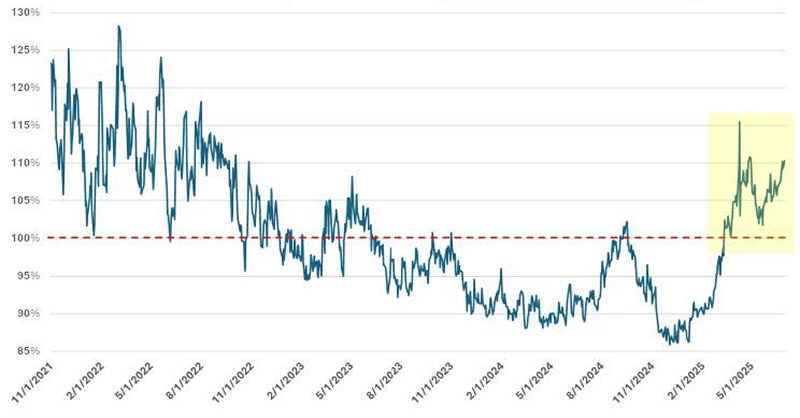

Another source of opportunity we're still aggressively capturing is the first genuinely attractive fixed income market since 2008. Headline yields across sectors continue trading at levels that provide solid levels of income, allowing bond portfolios to serve a valuable risk-reducing role within an overall asset allocation strategy in a way that simply wasn't possible in the long running ZIRP (Zero-Interest Rate Policy) era that prevailed during the 2010s.

Corporate bond portfolios with 3-8 year laddered portfolios can still be constructed with weighted average overall yields north of 4.50%.

Meanwhile the value in long-term municipal bonds continues to be plainly apparent, as high-grade/highcoupon munis with 7-10 years of call protection continue to be available at 4.50%+ tax free yields. That's generally equivalent to 7-9%+ pretax yields - which is also roughly on par with expected average long-term returns from the equity markets. These kinds of levels don’t come around very often, and they tend not to stay for long.

Moreover, tax-exempt long-term muni yields are currently yielding more than federally taxable 10 Year Treasury bonds, historically a good signal of relative value.

Our overarching thesis is plain and simple: the same equity and fixed income themes you've seen at work in your portfolios for 1H 2025 is largely how we're still allocating assets today, as we still find the riskreward proposition attractive.

Within equity allocations, as discussed earlier, we're continuing to monitor developments out of Washington and how they are (or aren't) translating into corporate earnings and consumer behavior. While we're wary of the richly valued stock market multiples and the potential for some economic weakness in 2H 2025, we continue to overweight large-cap tech and utilities, as both are well-placed to capture the benefits from the adoption and buildout of AI, re-onshoring of manufacturing, and growth in electrification.

Meanwhile we're still pounding the drum hard on the value of bond portfolios, and especially long-term munis. Just a few short years ago we remember authoring white papers about the 'changing role' of bonds within client asset allocations - back in the ZIRP era (short-term) bonds could only serve as portfolio 'ballast,' preserving principal and providing easily-accessible liquidity but no longer offering anything that could be described as real 'income.' We couldn't be happier that this is no longer the case, as the opportunities before us now remind me of the fixed income investment landscape of decades past. It's refreshing to see what's old is new again - at least for us.

At all times, we go about our work prioritizing the return of capital as more important than the return on capital. When constructing each client's asset allocation, we weigh the attractiveness of stocks/ alternatives/riskier assets vs. those available in other, less volatile investments. The guiding principle isn't complicated - minimize the overall risk exposure we need to accept in order to meet a reasonable annual return target. Right now, we're able to use 4.50% high-grade munis and corporates as the 'less risky' level that everything else is benchmarked against, a sufficiently high hurdle that has allowed us to 'de-risk' overall asset allocations, where appropriate.

Stated plainly - the greater the proportion of the overall return target we're able to lock-in through drama-free, well-structured bond portfolios, the less volatility we'll have to experience overall, with little sacrifice of after-tax returns. As a passionate fisherman, I often say we don’t have to leave fish to find fish - good and obvious opportunities are here in plain sight. We're currently finding the most 'optimum' asset allocation is barbelled, with concentrations in both long-term municipal bonds (corporate bonds for our tax-insensitive clients) and innovative large cap technology stocks.

We wish our clients a restful and refreshing summer.