As 2024 rounds the halfway mark, how are the economy, bond yields, and corporate credit fundamentals holding up after two-plus years of monetary tightening? Read on for our latest thoughts.

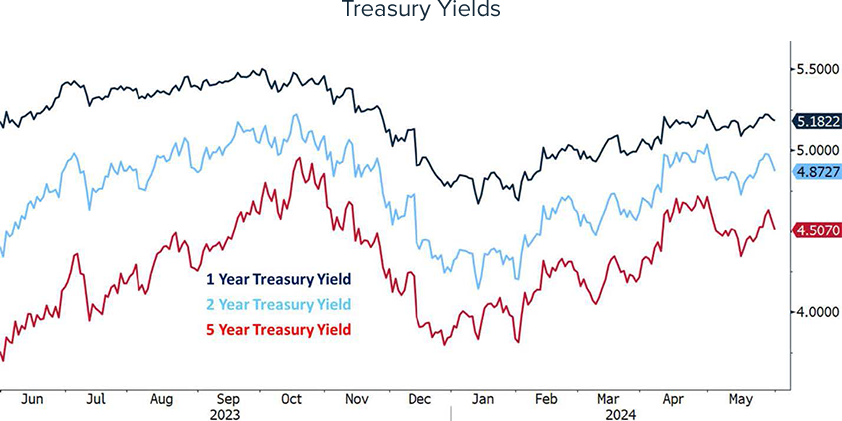

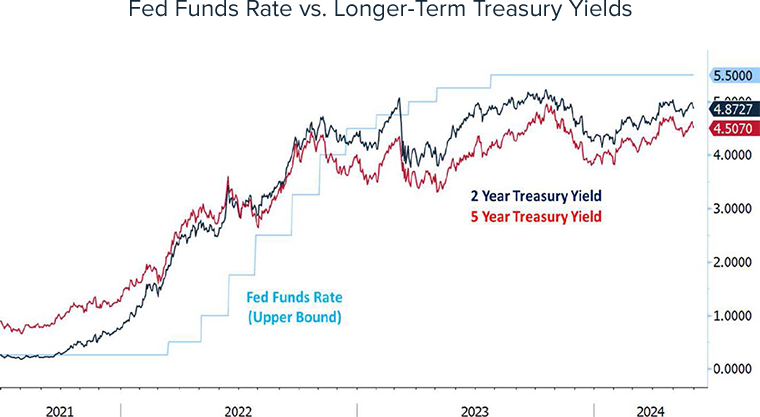

Through mid-year, we have witnessed diverging trends within the Treasury curve. While the shortest maturities have hardly budged (3-month bills have traded between 5.35-5.40% practically all year), yields on the longer 1 to 5-year maturities have increased notably.

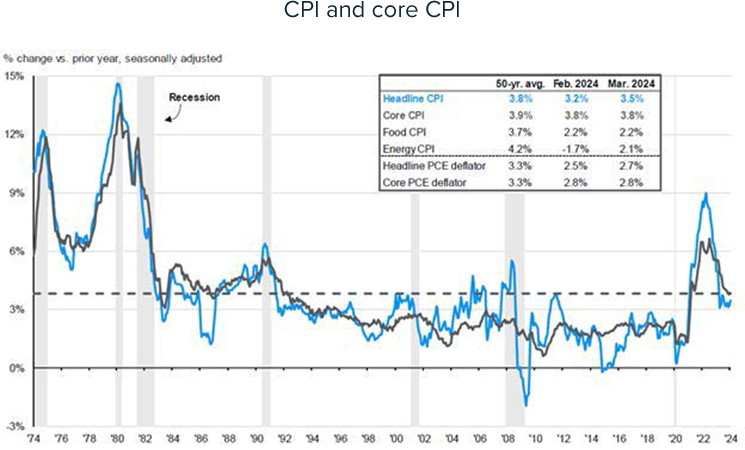

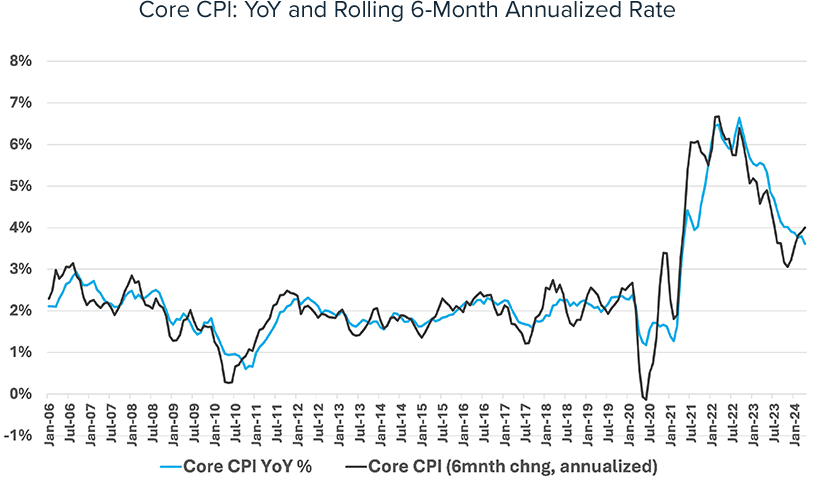

The key driver has been healthy incoming economic data that has forced the Fed and investors alike to reassess their previously ambitious rate-cut expectations. Perhaps the most surprising development for the consensus view is that inflation (which was expected to steadily continue on a downward trend) has clearly encountered resistance well above the Fed's 2% annual target rate.

But this does not come as a surprise to us, as we have long assumed that the disinflationary process would become rougher once the low-hanging fruit had been picked.

Keep in mind that this narrative might have further room to run in the months ahead, as the 6-month annualized rate of Core CPI (a timelier representation of current trends than the YoY measure) has now begun inflecting higher, and now sits close to 4%.

If you travel 1,000 miles to go fishing, the most important aspect is the last 30 feet where you're presenting the fly to the fish…Inflation has come down, yet the final stage in moving it towards [the Fed's] anticipated goal of 2% is not occurring."

Source: Richard Saperstein “Inflation Surprise Rattles Markets”, The Wall Street Journal, 4/10/24

These 'sticky' inflation prints are at least partially attributable to the real economy's surprising resilience. Corporate America has successfully managed to keep growing earnings and defend already-high margins (more to come on that later). In addition, the American consumer - the domestic economy's workhorse - is still quite healthy:

Unemployment remains low and job openings are plentiful.

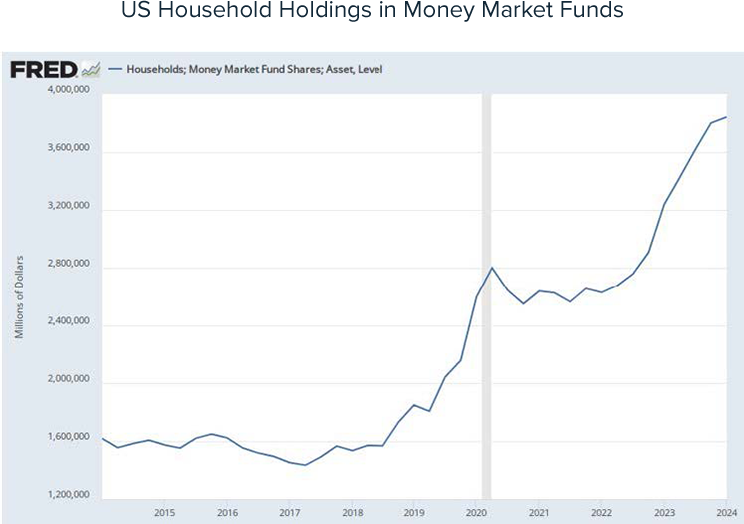

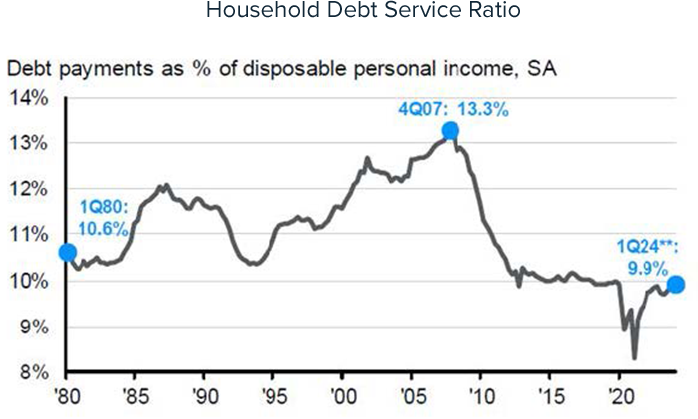

Although there is a case to be made that the pandemic-era 'excess' savings have been exhausted, household finances are nonetheless in good shape. MMF balances are still at all-time highs while debt service burdens are low.

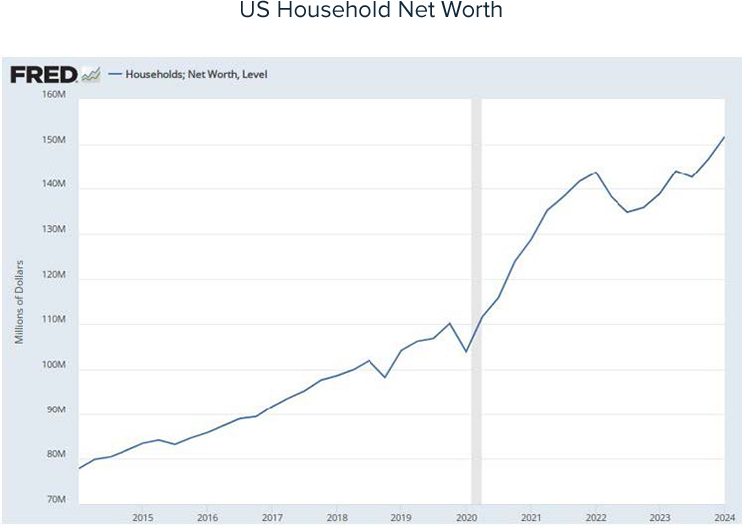

Americans' aggregate net worth has also more than made up for the pandemic-era dip, recently surging to a new record of over $150 trillion.

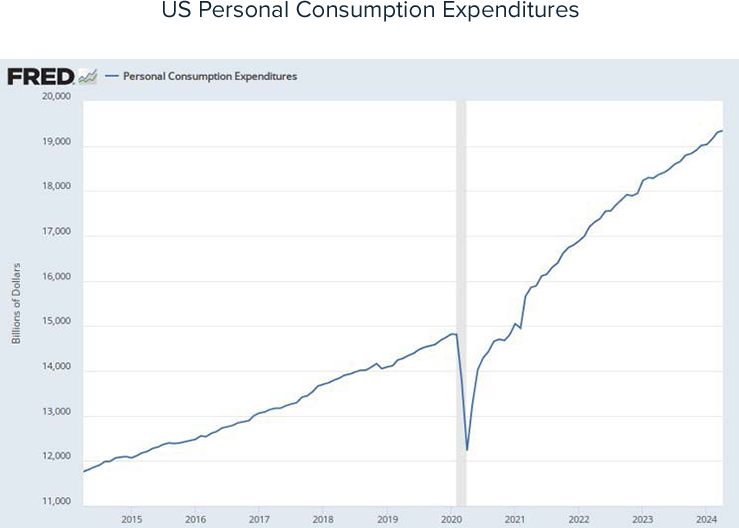

Given these strengths, it is no wonder that consumer spending is still healthy.

With household balance sheets strong, consumption is elevated and likely the most significant headwind for disinflation, impairing prospects for meaningful progress closer to the Fed's 2% target.

The upshot of all this robust inflation and economic data is that consensus Fed expectations have gradually shifted from anticipating as many as six rate cuts by the end of 2024 to now assuming just two cuts. This, in turn, is the primary factor behind the Treasury curve's persistent inversion, now easily the lengthiest in modern times.

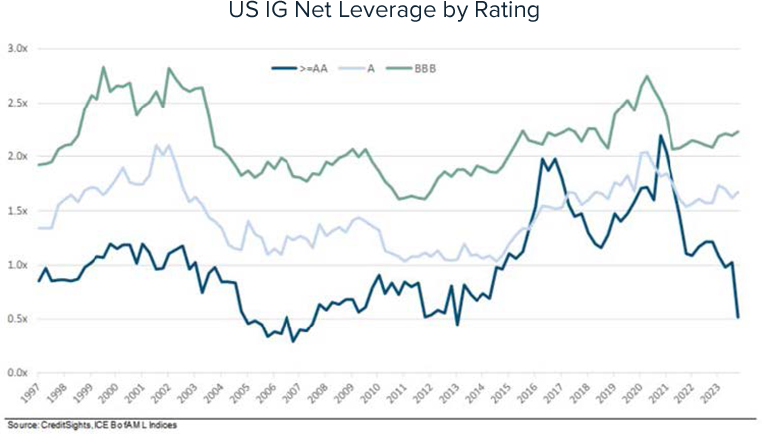

Given the steep rise in rates, is there evidence that the higher cost of financing has negatively affected corporate credit fundamentals? At least in the aggregate, the answer is 'No' –the higher-rate environment has thus far had only a muted impact for most Investment-Grade (IG) corporate bond issuers, as many companies have largely mitigated the harmful effects with prudent balance sheet management in preceding years.

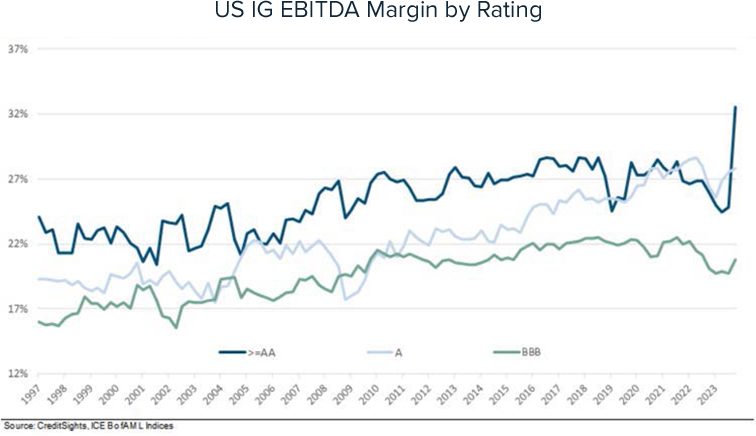

From a top-down perspective, what jumps out to us is the strong evidence of stable (or even improving) profit margins and leverage metrics.

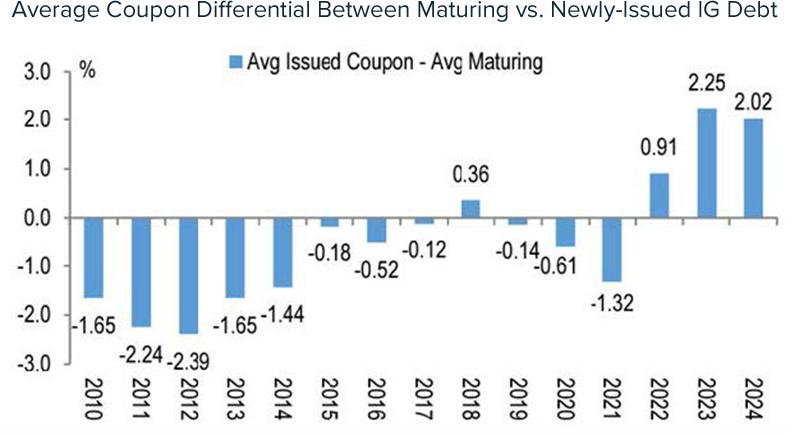

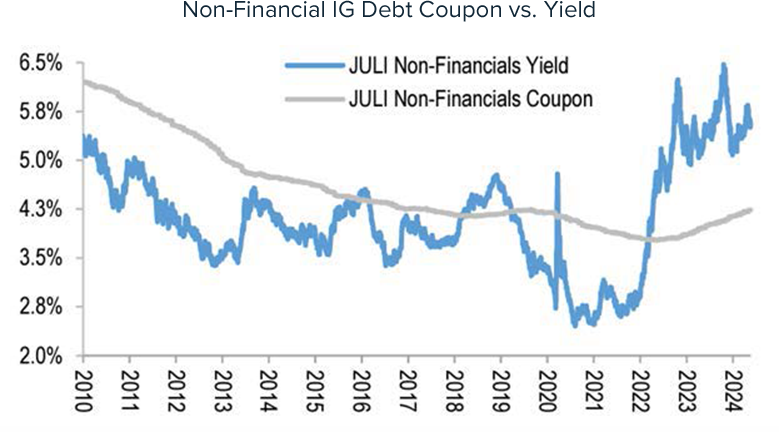

To be sure, the cost of financing has undeniably increased, as the average coupon on newly-issued debt is approximately 200 bps higher than that of maturing debt.

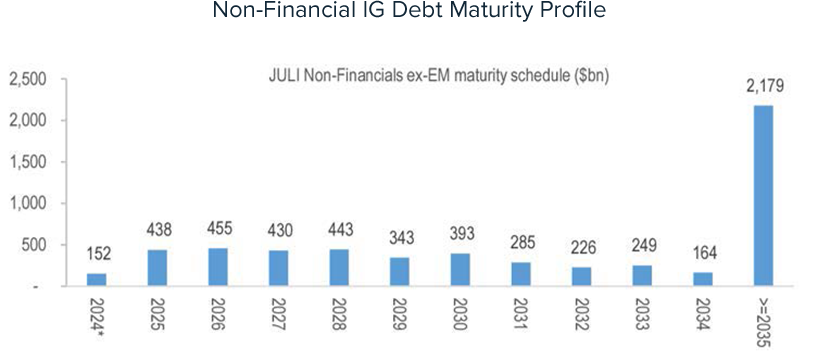

But maturity structure is key, and IG corporate debt maturities are generally well-distributed: that is, without any looming walls and with much of the outstanding lower-coupon maturities extended out several years. Even for those companies that will have to refinance at least a portion of their outstanding bonds soon, the estimated increase in interest expense is clearly manageable.

This favorable lag effect means that the average outstanding coupon within the investable IG universe is increasing at a slow and steady pace that's just a fraction of the much sharper increase in market yields.

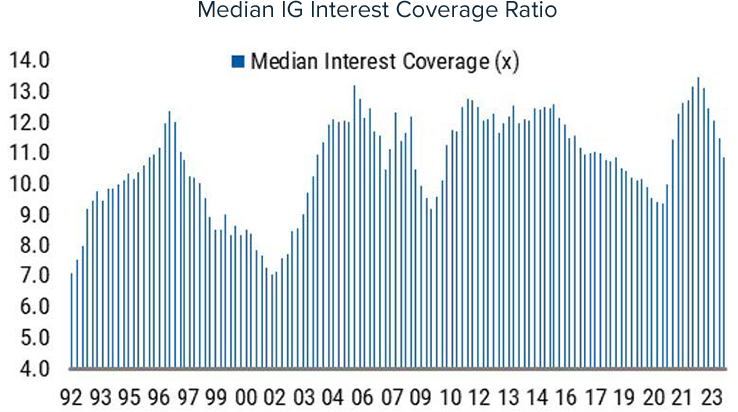

Clearly interest expense, while rising, is well under control, and does not face a looming near-term spike even if base rates stay elevated. Even better, interest coverage ratios remain solid versus their pre-pandemic levels.

The market has recognized these strengths and reacted accordingly: despite a 40% YoY increase in new issuance, the supply of new bonds has been easily digested, and short-term spreads have stayed tight while those on longer maturities have steadily drifted lower.

To summarize, fundamental credit quality of the IG universe remains robust, and we remain comfortable owning HG corporates for corporate cash clients within this elevated rate environment.

The case for major rate cuts seems flimsy; we simply are not seeing the kind of data that justifies the need to substantively ease monetary conditions (not least because fiscal policy is still extraordinarily supportive). Accordingly, we think the current market assumption of approximately two rate cuts by year-end feels about right, with the risks skewed more towards no cuts in 2024.

The optimal strategy for investing in this kind of environment depends on the existing state of the portfolio:

For portfolios that have already extended weighted-average maturities (WAMs), rolling short-term maturities (e.g. Treasury bills) makes sense for now. The curve is inverted and this captures the highest-yielding segment. As regular maturities roll off the short-term ladder, dry powder will become available should a better opportunity to consider extending and maxing out WAMs becomes apparent once more.

For clients that are fully liquid, we would employ a barbell structure, with bonds positioned in both very short-term paper and towards the longer end of investment policy limits. This provides regular dry-powder to take advantage of any potential rate increases, but also some 'ballast' that locks in a portion of the portfolio in case the economy falters and the Fed cuts more aggressively than anticipated.

Although it is not our base case, we recognize that recent data reflecting weakness in the lower-end consumer could ultimately portend a slowdown. Conversely, higher yields are a distinct possibility in the coming years, given the huge financing requirements of the federal government's massive budget deficits. In environments with significant uncertainty and starkly different potential outcomes, it pays to hedge your bets.